There has been a flurry of news reports about malicious actors taking advantage of the COVID-19 pandemic to steal personal and financial information from victims. Bleeping Computer recently reported that malicious actors were sending fake invitations to get vaccinated by the UK National Health Service. To receive their vaccine, the victims were asked to share their personal information, enabling malicious actors to target them with identity theft, and financial fraud.

Another story from the Netherlands explains that employees from the Dutch Municipal Health Service had put up for sale screenshots of personal files of Dutch citizens, including their names, addresses and social security numbers. The fraudsters were apparently taking pictures of files on their computers and reselling them on Wickr, Snapchat and Telegram. This news story confirms one of these chat messaging applications’ dirty secrets.

These platforms offer little to no ability to build an online persona. After a few days or after being read, the content on the applications can disappear. It is therefore difficult for vendors to set up an official shop with activity history that potential buyers can evaluate. As a result. vendors must share more information about what they are selling to prove they can be trusted. In this case, the vendors posted screenshots of their work computer screens. Once alerted by a news report, it was trivial for law enforcement to identify the employees and arrest them. The staff were in their early twenties, and possibly not very sophisticated malicious actors. Yet, if these employees were arrested, it is mainly because of their own actions, and their carelessness in publishing leaks that could be traced back to them.

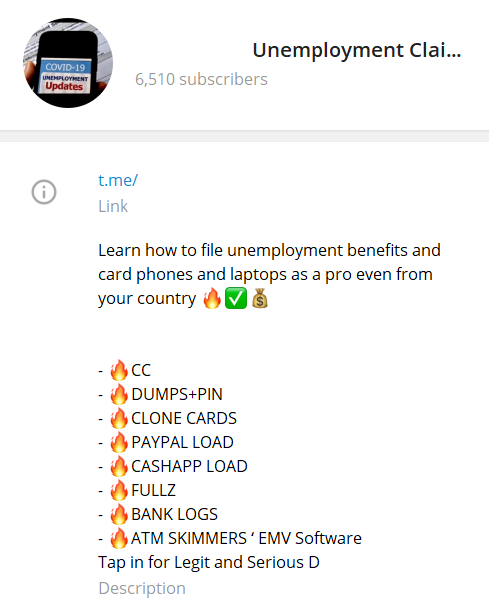

Another takeaway is that law enforcement did not detect this fraud operation, and only got involved once national attention was drawn to the problem by a journalist. It is well known that established criminal communities use Wickr, Snapchat and Telegram. Many of the chatrooms they use are geared towards malicious actors from a specific country, and discussions are held in that country’s language. The above screenshot is an example of a chatroom where malicious actors buy services to take advantage of unemployment claims in an industrialized Western country.

The fact that a news report was needed for law enforcement to take action demonstrates the complexity of the problem. Given there are countless chat rooms, each with hundreds or thousands of members, it can be difficult for law enforcement to monitor all offenders, and to track even the low hanging fruit that is publishing incriminating evidence.

The last takeaway from this news story is that everyone should be aware that their personal information sits in dozens of databases, often without their direct consent or knowledge. With massive vaccination efforts being launched, countries like the Netherlands are creating new databases with their citizens’ medical information. It is important to question who has access to that data, and if all necessary precautions were taken when hastily setting up those systems.

Who has access to what information is quickly becoming an important question in Canada, in light of recent legislative changes. This week, privacy commissioners found that a U.S. company that scraped names and photos of Canadians without their knowledge and consent on social media sites violated their privacy. While the data in that case came from private organizations, the question of how personal data is shared and collected is now central to Canadians’ concerns. Fortunately, we have yet to hear about a similar case of a COVID-19 database being abused in Canada, and resold on anonymous chat rooms. The Dutch experience, however, suggests that vigilance is essential to quickly identify any leaks, and that we may not be immune from young employees seeking to make a quick buck by reselling your data to the highest bidder.