Assaf Morag, Cybersecurity Researcher

For years, there’s been a saying in the security world: hackers don’t need to hack anymore – the keys are handed to them on a silver platter. But is that really true?

That question is what sparked our research into exposed secrets on Docker Hub. We designed a methodology to analyze leaked credentials, validate which were real, and investigate their origin:

- who they belonged to

- the environments they granted access to

- the potential blast radius to both the affected organizations and the wider ecosystem

In this report, we’ll also explore mitigation strategies and explain how Flare customers benefit from this research – using an automated API-based scanning engine and in-platform detection workflows that identify and protect against secret exposure.

Key Findings

- More than 10,000 Docker Hub images contained leaked secrets (including live credentials to production systems) found in just one month of scanning

- Over 100 organizations were exposed, including one Fortune 500 company and a major national bank, but many had no awareness of the breach

- 42% of exposed images contained five or more secrets each, meaning a single container could unlock an entire cloud environment, CI/CD pipeline, and database

- AI LLM model keys were the most frequently leaked credentials, with almost 4,000 exposed, revealing how fast AI adoption has outpaced security controls

- A significant portion of leaks came from shadow IT accounts – personal or contractor-owned registries – completely invisible to corporate monitoring

- Developers often removed leaked secrets from containers, but 75% failed to revoke or rotate the underlying keys, leaving organizations exposed for months or years

- The findings confirm a new attack paradigm: attackers don’t hack in – they authenticate in – using keys that companies accidentally publish themselves

The Position of Secrets in the Modern SDLC

In modern organizations’ Software Development Life Cycle (SDLC), secrets are the connective tissue of the digital supply chain. They enable authentication, automation, inter-service communication, and machine-to-machine trust across cloud providers, CI/CD pipelines, messaging platforms, and developer tooling.

Everything from infrastructure provisioning to artifact publishing relies on keys, tokens, and certificates. As companies adopt microservices, ephemeral infrastructure, serverless architectures, and federated development models, the number of secrets in circulation has exploded.

A single application can require dozens of API keys spanning vendors like AWS, GitHub, Slack, Stripe, GCP, and internal services, etc. Often, these credentials remain valid long after a developer has left the project or the organization.

But while secrets are foundational to automation, they are also dangerously fragile. Their power often exceeds their visibility. Many organizations have thousands of active secrets that are never audited, scanned, rotated, or centrally managed. In practice, secrets become scattered across:

- source code

- config files

- developer laptops

- build pipelines

- container images

- personal cloud accounts

Some of these secrets can reach deep to control production environments, cloud accounts, and even the very core of a company. This creates a silent attack path where a single exposed token can bypass MFA, circumvent perimeter defenses, and provide direct privileged access into production systems. In essence, secrets are both the lubricant of modern engineering and the Achilles heel of organizational security, as they are easy to use, easy to forget, and devastating if exposed.

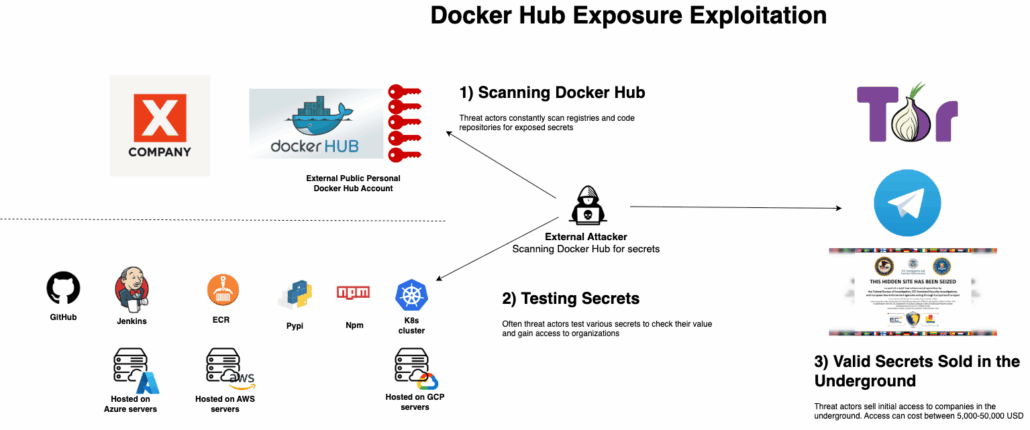

Attack Scenarios and Potential Impact

Across these incidents that were widely published in the media there’s a clear pattern: attackers don’t need to exploit zero-days or break sophisticated encryption. Instead, they simply wait for organizations to leak their own secrets, then ride those credentials straight into code repositories, CI workflows, and even production cloud accounts.

Whether it’s Shai-Hulud harvesting developer tokens from compromised packages, a backdoored GitHub Action scraping CI/CD secrets, or companies like Microsoft and Toyota accidentally committing cloud credentials to public repositories, the underlying failure is consistent: secrets are treated as static and immortal rather than dynamic and short-lived, and there is insufficient automated detection of credential leakage at the moment of exposure.

This model illustrates that today’s supply-chain and cloud breaches are not random – they are structurally predictable, preventable, and propagate through the weakest link: credential hygiene.

Diagram of Docker Hub exposure exploitation

The Shai-Hulud 2.0 NPM Worm

Shai-Hulud 1.0 began as a malicious NPM supply-chain worm that infected legitimate packages with post-install scripts to steal developer secrets and spread itself using compromised NPM/GitHub credentials, pushing malicious code into downstream ecosystems and making private repos public.

Defenders initially mitigated by clearing caches, rotating credentials, and inspecting GitHub activity – but Shai-Hulud 2.0, launched in November 2025, introduced far more advanced capabilities: shifting execution to preinstall scripts, using Bun-based payloads to evade detection, scaling to hundreds of compromised packages and tens of thousands of repositories, improving secret exfiltration via creation of public GitHub repos, and achieving cross-victim lateral propagation.

This evolution transformed Shai-Hulud from a clever credential-harvester into a highly adaptive global supply-chain worm. More details here.

GitHub Actions tj-actions/changed-files Supply Chain Breach

In mid-March 2025, a massive supply-chain compromise hit GitHub when a popular GitHub Action tj-actions/changed-files was backdoored and modified to print CI/CD secrets (PATs, keys, registry tokens, cloud credentials, etc.) directly into workflow logs, silently exfiltrating them across thousands of pipelines.

Investigators later traced the breach to a leaked SpotBugs Personal Access Token, which attackers leveraged through a vulnerable workflow to gain write access, escalate privileges, and pivot through dependent repositories and actions. The campaign’s initial focus on Coinbase’s open-source agentkit highlights the attackers’ strategy: compromise a critical CI/CD link, harvest secrets at scale, and weaponize exposed SDLC infrastructure to enable deeper downstream intrusions.

This illustrates how a single key can be leveraged by attackers to have a massive impact on the entire development ecosystem. More details here.

Microsoft Azure SAS Key Leak – Unauthorized Access to Internal AI Data

In 2023–2024, Microsoft faced a major cloud security exposure when a GitHub repository inadvertently contained a broadly permissive Azure SAS (Shared Access Signature) token granting full access to internal storage accounts used for AI training data.

This token allowed anyone who found it to browse private datasets, download confidential material, and even write or modify storage containers and blobs within Microsoft’s Azure environment. The exposure forced Microsoft to rapidly rotate the compromised access credentials and implement stricter internal controls on repository scanning, secret management, and key governance to prevent future leaks.

Toyota AWS Credential Exposure – Years of Silent Cloud Access

During the same period, Toyota experienced its own damaging cloud security lapse when AWS credentials were accidentally pushed into a public GitHub repository, unintentionally granting access to its cloud-hosted vehicle telematics system.

Threat actors used those keys to access data belonging to more than 2 million Toyota vehicle owners, including location-based telemetry, GPS information, and safety-related records. The key had reportedly remained valid for years, meaning the exposure likely allowed persistent unauthorized access and highlighted systemic credential hygiene failures across Toyota’s SDLC practices and cloud security posture.

Research Methodology

We defined 15 distinct types of secrets spanning the Software Development Life Cycle (SDLC), cloud infrastructure credentials, and AI model access tokens. These key types were initially chosen as representative samples (not exhaustive) and the research quickly enabled us to expand this list into hundreds and potentially thousands of additional exposed credential types circulating in the wild.

In fact, our findings directly enriched our detection models and enhanced our ability to uncover and contextualize further exposed secrets.

Below is the specific set of key types we focused on:

- SDLC & Source Control Credentials:

GITHUB_TOKEN, BITBUCKET_APP_PASSWORD, ECR_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY, NPM_TOKEN, PYPI_API_TOKEN - Cloud Service Provider Credentials:

AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY, GOOGLE_OAUTH_ACCESS_TOKEN, AZURE_CLIENT_SECRET

AI & Model Access Tokens:

OPENAI_API_KEY, OPENAI_TOKEN, HF_TOKEN, HUGGINGFACE_API_KEY, ANTHROPIC_API_KEY, GEMINI_API_KEY, GROQ_API_KEY

All scans were conducted on Docker Hub container images uploaded within the past month (November 1st-November 30th, 2025). In total, we identified 10,456 container images containing one or more exposed keys. After filtering out findings below High and Critical severity, we were left with 205 distinct namespaces on Docker Hub.

We chose Docker Hub because we maintain a dual-indexing approach:

- We index Docker Hub manifests, similar to other organizations.

- We also pull and unpack container images, extract the files, and scan them for sensitive data, then index those findings. To our knowledge, no other provider performs deep file-level extraction and secret scanning at this scale.

During our investigation, we analyzed the 205 namespaces and successfully associated 101 of them with identifiable companies of varying sizes, primarily small and medium businesses, though a few large enterprises and even one Fortune 500 organization appeared in the dataset.

Identification was performed by correlating namespace ownership with known company entities; the remaining namespaces were categorized as personal accounts. Interestingly, we found several cases where founders, contractors, freelancers, or employees were pushing container images from personal Docker Hub accounts, unintentionally exposing company secrets in the process.

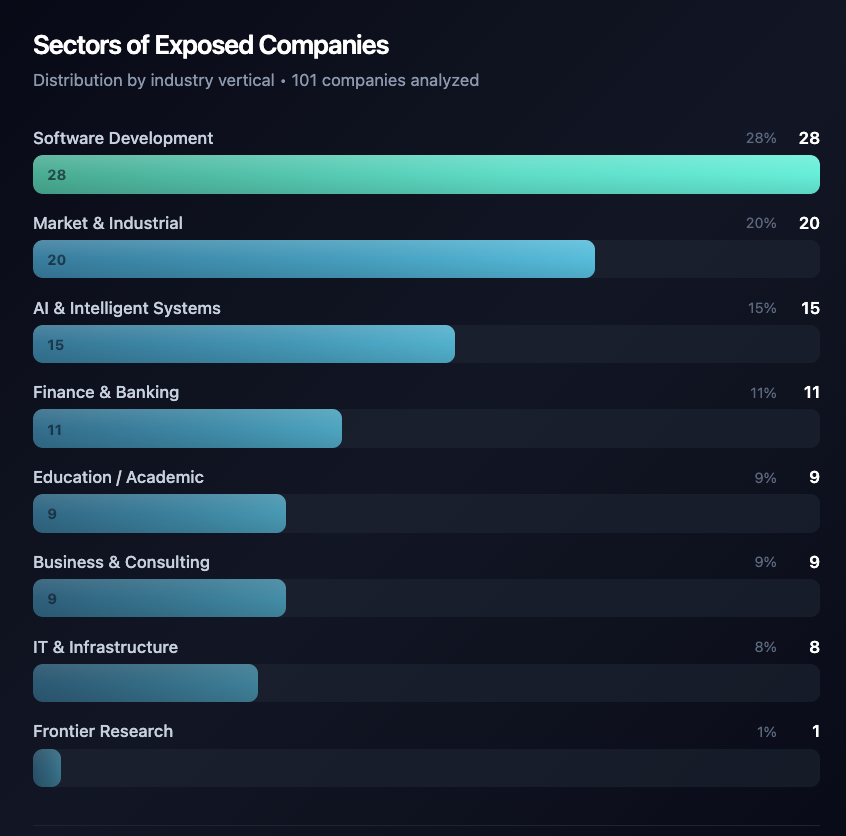

Below is a breakdown of the business sectors represented by the 101 identified companies:

Top sectors of the 101 exposed companies

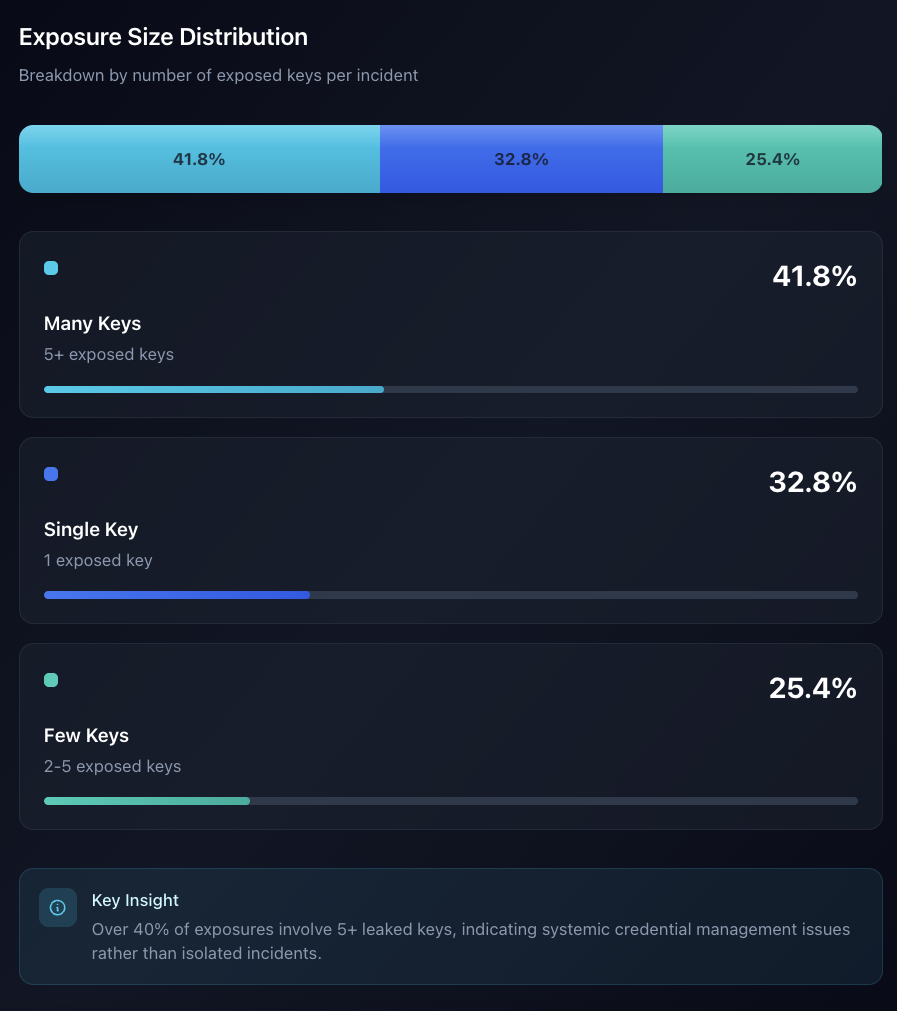

A particularly alarming insight emerged when examining the exposed secrets: approximately 42% of the leaked container images contained five or more sensitive values. These multi-secret exposures represent critical risks, as they often provide full access to cloud environments, Git repositories, CI/CD systems, payment integrations, and other core infrastructure components.

Distribution of Exposure Size by Number of Exposed Keys

Below you can see a further breakdown of the secrets found:

| Category | Docker Hub Accounts | Meaning |

| AI | 191 | AI API’s Grok/Gemini/Anthropic, etc. |

| CLOUD | 127 | AWS/Azure/GCP/Cosmos/RDS secrets |

| DATABASE | 89 | Mongo / Postgres / Neon / ODBC / SQL creds |

| ACCESS | 103 | JWT / SECRET_KEY / APP_KEY / encryption |

| API_TOKEN | 157 | Generic 3rd-party API keys |

| SCM_CI | 44 | GitHub / Bitbucket / NPM / Docker |

| COMMUNICATION | 31 | SMTP / Sendgrid / Brevo / Slack / Telegram |

| PAYMENTS | 21 | Stripe / Razorpay / Cashfree / SEPAY |

Additional search for a comparison of AI secrets showed that with filtering only based on the scanning of Docker Hub images from the past 1 month (November 1st-November 30th, 2025) and only high and critical severity, there were almost 4,000 AI keys exposed.

Moreover, we identified 10 NPM access keys, of which three were linked to medium-sized companies with a significant volume of NPM package downloads.

Identifying a Company

- Connecting a Docker Hub account to a company can be a very easy task or an impossible one, depending on the available and hidden data in the registry. The easiest way was to check the details on Docker Hub: Sometimes it’s a company, and then you have email, website, and more information.

- The names can be indicative: It’s not a company, but if the name is Company X Ltd, the name can point you to the company.

- Digging deeper: the process of validation was much longer and tighter, based on several strong indicators like domain names, IP addresses, namespaces, and further identifiers inside the code itself. If we had less than 80% confidence (based on various factors we defined), the identity was set; otherwise, we marked it as unknown.

Reflecting on Our Findings

We can classify the findings concerning the identity of the owners of the accounts into three main categories:

- Organizations and companies leaking secrets

- Personal accounts leaking personal secrets

- Personal accounts leaking companies’ secrets

Exposure of Companies

Modern SDLC workflows rely on a vast number of secrets to support highly automated and distributed development pipelines. Developers routinely use cloud keys, API tokens, model-access credentials, database connection strings, and CI/CD tokens to enable seamless integration between tools and environments. Containers have become the backbone of this ecosystem, packaging dependencies, runtimes, and microservices into portable units that flow between development, build, testing, and production stages.

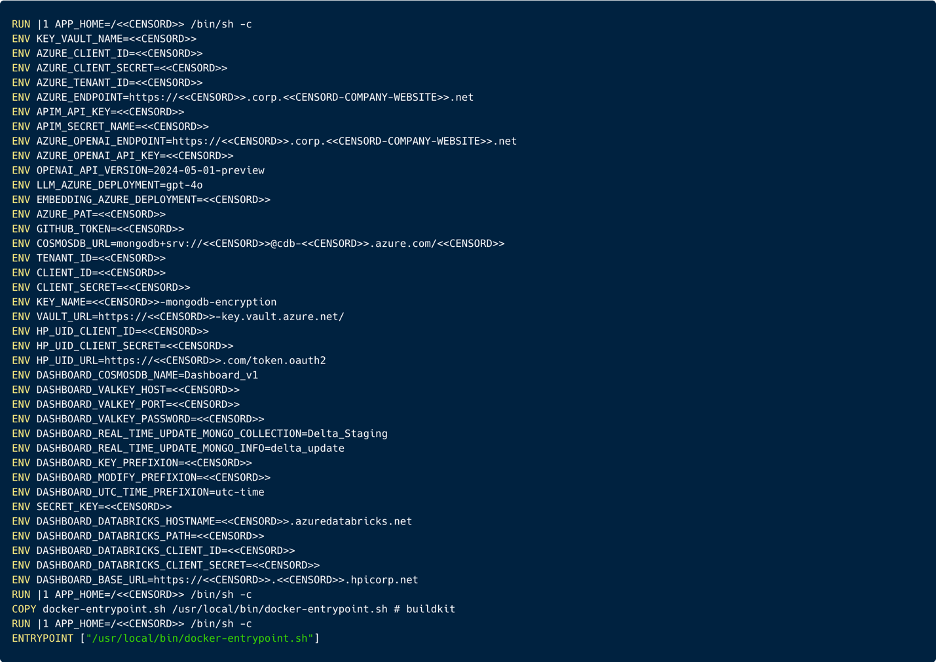

Consider a real-world example involving a company that specializes in tailoring AI models to fit the unique business and technical needs of its customers. In this case, the organization unintentionally leaked a GitHub token by embedding it directly within a Docker Hub container manifest.

The exposed GitHub token was not restricted, it had full administrative privileges across the company’s repositories, organizations, and package registries. Its scope included high-risk permissions such as write:packages, delete:packages, repo, delete_repo, admin:org, and even admin:enterprise. With this level of access, an attacker could push or remove packages, alter GitHub Actions pipelines, delete repositories, and modify critical organizational configurations. In effect, the token granted complete, god-level control over source code, CI/CD workflows, secrets, and supply-chain artifacts.

The implications extend far beyond the exposed organization itself. A compromise of this magnitude could provide an attacker with an initial access foothold into the environments of downstream customers—particularly those consuming models, packages, or automation workflows distributed through affected repositories. In other words, one leaked token becomes a potential supply-chain compromise multiplier with cascading impact across the organization’s entire customer ecosystem.

Exposure of Personal Secrets

There are many examples of personal accounts with side projects and private environments. These are usually characterized by a single secret exposed of a lot of secrets all together that put the person and its technological stack at severe risk.

Exposure of Personal Affiliations to Companies

While corporate registries are often heavily monitored by utilizing secret scanners, SAST and SCA, and other tools, the external accounts that contain company’s secrets, or more properly Shadow IT accounts, are hardly monitored at all. This may lead to years of exposure without having the knowledge or the ability to find and remediate this situation. Below are some examples of actual cases that were highlighted during our research:

In one case, we correlated a Docker Hub public account to a website of a contractor developer. He works as a freelancer and provides project-based services for small businesses to develop websites or applications for them. The Docker Hub account contains 70 repositories, ~45% of the container images are being updated continuously, including in the past 30 days, ~35% were updated during the last year, and the rest were older.

The container’s structure is the same; a specific file within the container’s filesystem contains dozens of keys and secrets of the environment.

Normally, it’s a cloud account access (AWS mainly), S3 buckets secret with access to the entire project logs of the activity and artifacts, a database (usually PostgreSQL), applications’ api keys and secrets, Google Analytics keys, and OpenAI keys.

These are all keys of the organization; they don’t belong to the freelance contractor, but they are out of the reach of the organization’s security controls and sensors.

In another striking case, we identified a Fortune 500 company whose secrets were exposed through a personal public Docker Hub account – likely belonging to an employee or contractor. There were no visible identifiers linking the repository to the individual or to the organization, yet the container manifests contained highly sensitive credentials with access to multiple internal environments. This case highlights a critical reality: organizations are increasingly at risk not through their official, monitored infrastructure, but through shadow and personal repositories that sit entirely outside corporate visibility, governance, and security controls.

I interviewed a senior DevOps engineer who has spent over a decade delivering tailored infrastructure and SDLC solutions as a freelancer. He described his workflow: “I typically work through a large contracting provider that supplies vetted freelance engineers to different organizations – from major tech enterprises to emerging startups.”

When I showed him a censored sample of the exposed secrets from our findings, he reacted immediately: “Oh, this is bad. This would never happen with the companies I work with. They assign you a full organizational identity and provide access keys only within their hardened environments. Many even ship you a secured company laptop with enforced VPN routing, endpoint monitoring, and strict security controls”.

Another case uncovered in our findings was particularly concerning: a container registry belonging to the chief software architect of a major national bank. The registry contained hundreds of container images, and several of them included exposed AI API tokens. While the presence of AI-related keys alone could be damaging, the more alarming issue was that over 430 container images associated with the bank were publicly visible, with no meaningful access control, auditing, or validation. In practice, this meant that not only the architect’s experimental or personal projects (but potentially core infrastructure components) were exposed to the global internet, creating a high-value attack path into one of the country’s most critical financial institutions.

Explaining these Findings from the Developers/DevOps Perspective

All of the leaked secrets described here were discovered in public Docker Hub repositories. The following example reflects a typical development workflow pattern for building and pushing Docker container images, and more importantly, the common mistakes that unintentionally expose sensitive information.

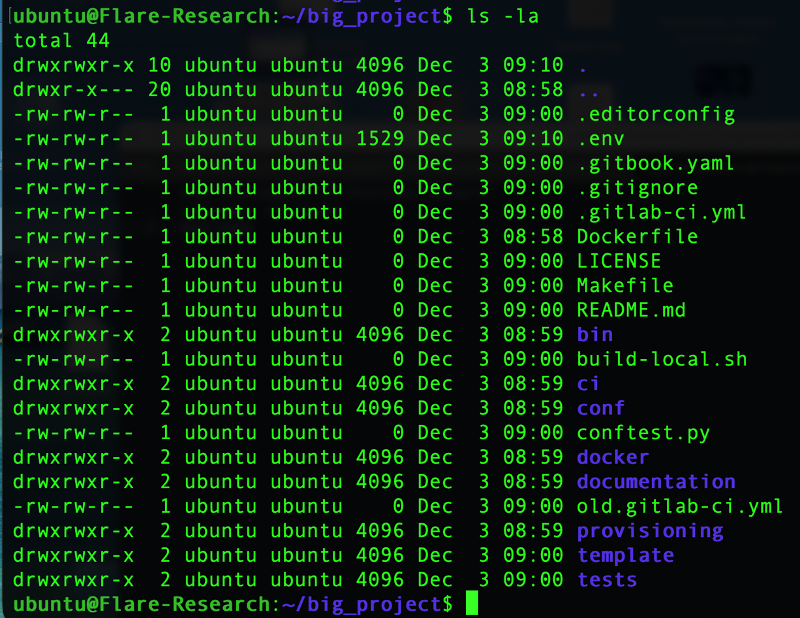

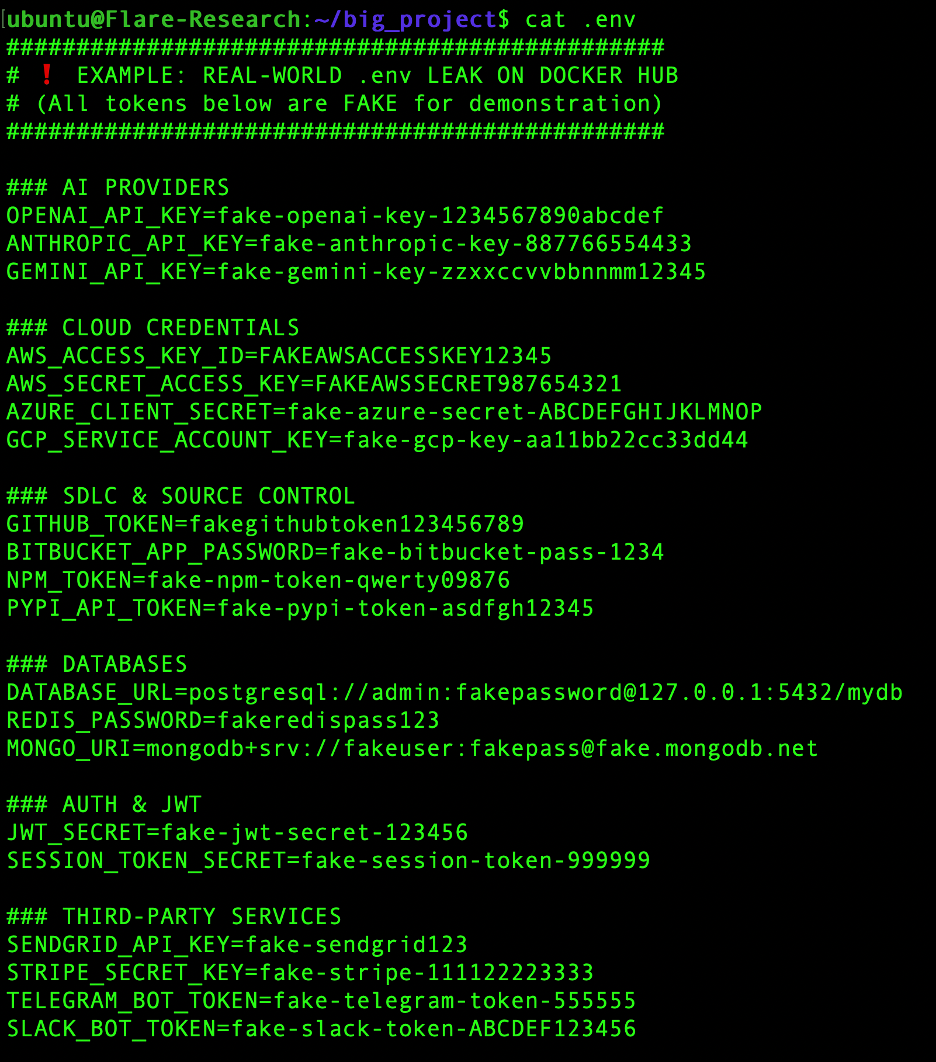

One of the most frequent errors we observed is the use of a ‘.env’ file to store environment variables and secrets during local development. Developers often create a .env file containing database credentials, cloud access keys, tokens, and other authentication materials necessary for running the project. For larger applications, this file may hold dozens of secrets spanning multiple external integrations. A typical project directory might look like:

This is how the content of a ‘.env’ file may look like:

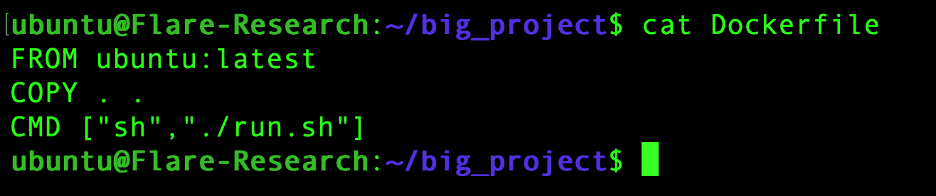

Then you will build this into a Docker container image, using a Dockerfile.

When the entire project directory is copied during the Docker build process, the ‘.env’ file is often included unintentionally, embedding all of its secrets directly into the container filesystem.

Even if the resulting image is stored in a private registry, this still represents a high-risk practice; a compromise of that registry would immediately expose those secrets and enable lateral movement throughout the organization.

An even more dangerous scenario is when such an image is pushed, intentionally or not intentionally, to a public repository. This is why it is critical to scan and sanitize container images for secrets before publishing them, whether they are intended to be private or public.

We repeatedly observed similar patterns of leakage through other file types as well. For example, Python application files containing hard-coded AI API tokens in plain text. These credentials were not encrypted, obfuscated, or protected in any meaningful way.

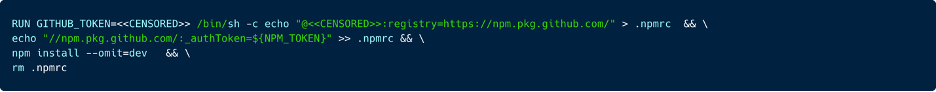

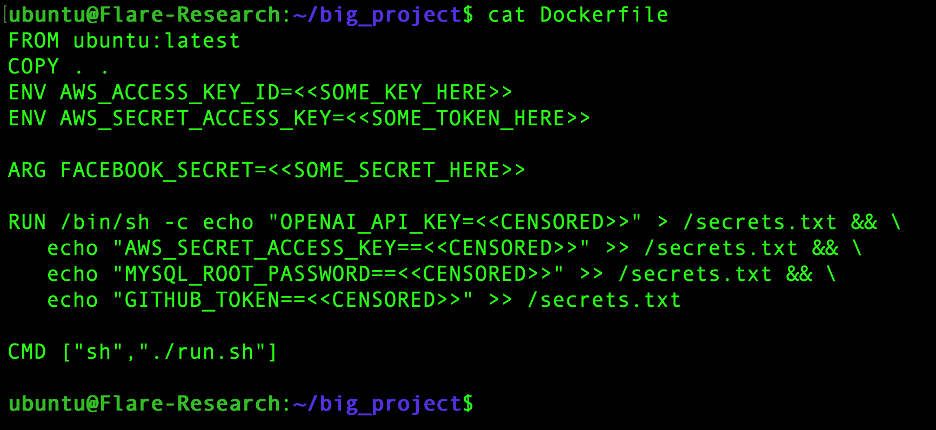

Another common exposure vector we found was the presence of secrets directly within the Dockerfile itself. In these cases, the secrets may not end up inside the container, but they are still exposed through the image manifest and visible on Docker Hub, effectively making them publicly accessible to anyone retrieving the image metadata.

When secrets are embedded in the Dockerfile or container context, they often become visible directly on the Docker Hub page, effectively exposed to the entire internet and routinely harvested by automated scanners, bots, and threat actors searching for initial access into victim environments.

But what happens when this exposure occurs by accident? Our research shows that approximately 25% of developers removed the exposed secret from their container or manifest within 1–2 days. While that response is encouraging, it is still insufficient, as in most cases, the associated credential was not revoked, meaning the key remained fully valid and exploitable even after the visible leak was “fixed”. Developers often believe the incident has been remediated simply because they deleted the reference – when in reality, the secret itself continues to function and remains in the attackers’ possession.

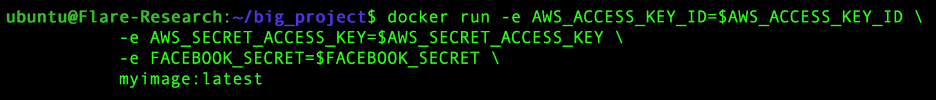

A far better practice is to avoid embedding secrets at build-time entirely. Instead, inject them only at runtime via environment variables – for example:

This approach eliminates static credential storage inside the container or manifest, significantly reducing the risk of accidental exposure – because the secrets never exist inside the registry or artifact at all.

Mapping the Campaign to the MITRE ATT&CK Framework

Our research showed how attackers in the past leveraged secrets to attack organizations. As part of the exposure, there are actual and potential common techniques leveraged by attackers following a secret exposure. Here we map each component that appeared in the blog to the corresponding techniques of the MITRE ATT&CK framework:

| Initial Access | Execution | Credential Access | Discovery | Impact |

| Valid Accounts (T1078) | Command and scripting interpreter: Windows (T1059.003) | Unsecured Credentials (T1552) | System Information Discovery (T1082) | Data Destruction (T1485) |

| Supply Chain Compromise (T1195) | Command and scripting interpreter: Unix Shell (T1059.004) | Credentials from Password Stores (T1555) | File and Directory Discovery (T1083) | Data Encryption (T1486) |

| External Remote Services (T1133) | Command and scripting interpreter: Python (T1059.006) | Create or Modify System Process (T1543.002) | Cloud Service Discovery (T1082) | Service Stop (T1489) |

| N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Resource Hijacking (T1496) |

A Tailored Solution with Flare

Since Flare is indexing multiple data streams from open-source, deep and dark web domains, including GitHub, Docker Hub, and Pastebin sites. In addition, Flare is also scanning various files, S3 buckets, and Docker Hub files inside the various layers of the container image, and it creates a perfect mixture of sources for potential exposed secrets, whether it’s from the organizational repository, a contractor, a freelancer, or an employee.

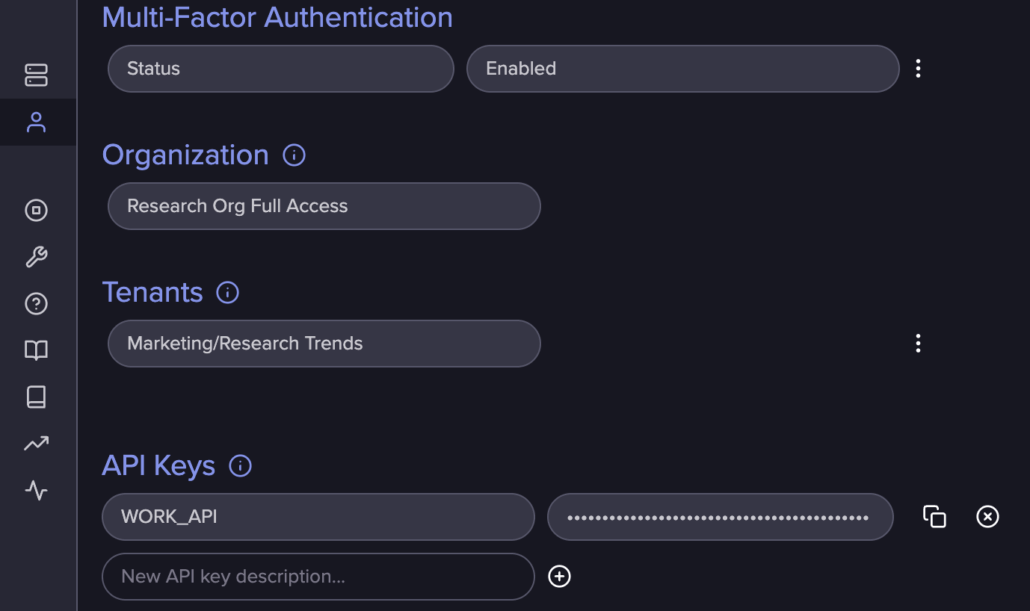

You can log in to the platform and start working on alerts. If your organization is small with few keys and tokens, you can follow this short process to define your alerts.

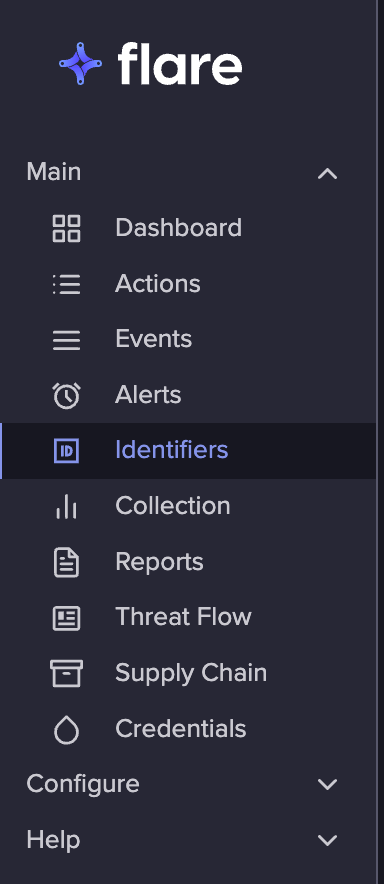

- Select identifiers. In the main pane, you should choose identifiers.

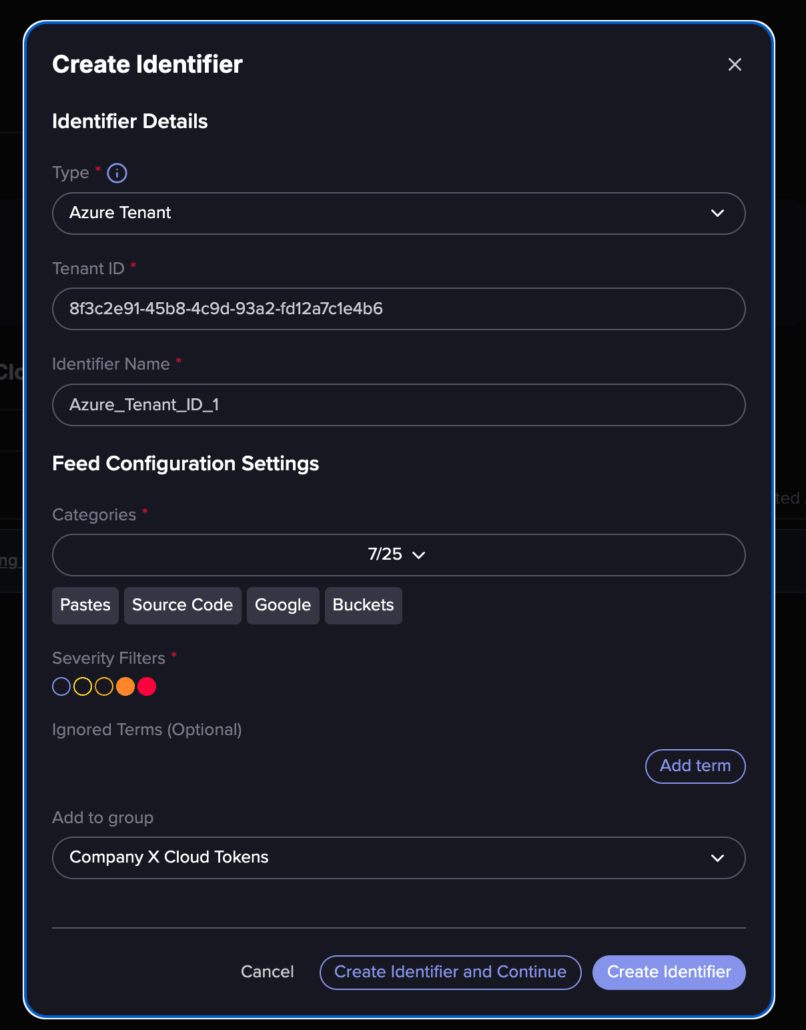

2. You can create identifiers. You can choose an Azure tenant out of the box option and define your tenant ID.

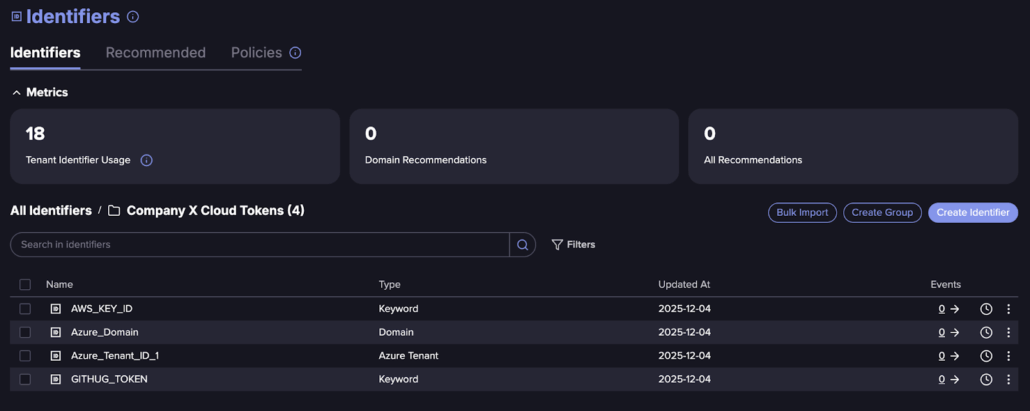

Like in the screenshot below, define a keyword, which can be a GitHub token, AWS key or anything you desire.

Lastly, you will get a list of identifiers like in the screenshot below.

3. Create a channel. Go to alerts and choose to create an alert. If you don’t have a defined channel (where the alerts will be sent), you will be required to create one. We chose to send the alert to our company’s security team email.

4. Create an alert. At this stage, you can define the alert and choose the appropriate severity level. We recommend using High or Critical when the alert does not target a specific key, secret, or domain. However, if you are configuring an alert for a specific value unique to your organization (such as a particular key, secret, or internal domain) you may assign any severity level that fits your operational needs.

That said, a more realistic scenario involves an organization managing hundreds or even thousands of API keys, tokens, and unique identifiers. By leveraging Flare’s API, you can register an API key and automate searches for your organization’s sensitive values at scale. For example, you can write a script that collects keys from your AWS, Azure, GCP, and other secret vaults, then queries the Flare API to check whether any of these keys have appeared in the wild. This approach provides continuous, programmatic monitoring for leaked credentials across the external threat landscape.

Mitigation Recommendations for Security Teams

The overarching truth revealed by our research is that secret exposure isn’t a rare accident – it is predictable and structurally systemic. Mitigation, therefore, must be systemic as well, spanning cultural practices, technical controls, and architectural redesign.

Never Store Secrets in Containers

No secret should ever exist inside a container image. Period.

Some secrets are:

- .env files

- Python files

- Config.json

- YAML configs

- Dockerfiles

- Workspace directories

- Component manifests on Docker Hub

If a container image contains a secret, it is already compromised. A container should only reference secrets externally at runtime.

Stop Using Static Long-Lived Credentials

Transcend to short-lived session-based auth. Long-lived tokens are the root cause of persistent risk. The modern defensive model is ephemeral identity. Organizations should replace:

- AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY

- long-lived GITHUB_TOKEN

- AZURE_CLIENT_SECRET

- service_account_key.json

With session-based access models such as:

- AWS SSO with IAM Identity Center

- AWS STS AssumeRole with MFA

- GCP Workforce Identity Federation

- Azure AD Managed Identities

- Keycloak OpenID Connect

- Okta / Auth0 ephemeral access tokens

These methods allow just-in-time access, time-limited keys, and prevent credential persistence.

Centralize Secrets Management

Developers often store secrets wherever it’s convenient. Instead, organizations must adopt centralized vaulting, such as:

- AWS Secrets Manager

- GCP Secret Manager

- Azure Key Vault

- HashiCorp Vault

- 1Password Connect

- CyberArk Conjur

Implement Continuous Scanning

Secrets are leaked during builds, debugging, CI/CD pipelines, during local testing, during containerization etc.

Organizations must scan multiple environments across various vendors and platforms, and technologies. Sometimes the practitioners who made the mistake delete the leak, but it often stays in mirror repositories, scrappers’ databases etc. So, you need to cover source repos, container images, package registries, commit histories, build logs, and ephemeral environments.

Thus, tools that allow you broad visibility and historic memory, like Flare’s API-driven secret detection, provide a better solution for such cases.

Once found, secrets should be detected and revoked before attackers find them, not after.

Enforce Immediate Revocation and Rotation Procedures

When a secret leaks, the clock starts ticking and attackers scan continuously – in minutes, not days. So best practice is:

- Automatically revoke leaked key

- Automatically rotate regenerated credentials

- Invalidate old sessions

- Audit logs for unauthorized access

Critical failure pattern from our research – around 25% of developers removed a leaked key from Docker Hub but did not revoke the underlying credential. They believed they were safe – they were not.

Gain Visibility into Shadow-IT

Monitor personal registries and contractor accounts. Our research showed a major blind spot.

Company secrets are frequently exposed through:

- Employee personal Docker Hub accounts

- Contractor repos

- Freelance developer assets

- Unmanaged external namespaces

Organizations need:

- External namespace monitoring

- Identity association heuristics

- Cross-registry surveillance

- Correlation of leaked domains, APIs, and internal paths

- Real-time discovery of “unofficial” artifact pipelines

Flare specifically enables this by scanning external containers and associating exposed keys with company identities – even when they originate outside official infrastructure.

Educate Developers

The shift left continues as organizations must constantly adhere to the shifting mindset and ownership. Posting keys in containers isn’t simply a technical error – it is a mindset error.

Developers must be trained:

- To never embed secrets in code

- To never store them on disk

- To never paste them into files for convenience

- To assume every environment is compromised by default

Monitoring Leaked Secrets with Flare

To dive deeper into these findings and understand how to protect your organization from large-scale credential leaks, join our upcoming verified practitioner session:

Mass Secret Exposure on Docker Hub: Key Findings and What You Need to Know

December 18th, 9:00–9:30 AM ET | Flare Academy Discord Server

Not yet verified? Become a Verified Community Member through Flare Academy to access exclusive research briefings, practitioner trainings, and hands-on resources.

Already verified? The event is listed in the Flare Academy Discord, with ongoing updates in the verified channel. We look forward to seeing you there.