By Assaf Morag, Cybersecurity Researcher

What began as an ordinary SSH brute-force attempt, one of the countless attacks that wash over the internet every minute, quickly turned into a threat-intelligence rabbit hole. A routine alert from our high-interaction SSH honeypot became the entry point to a broader investigation, pivoting through dark web forums, Telegram channels, and open-source development platforms.

We documented a real-world attack chain that started with credential brute-forcing and evolved into a deep dive into attacker infrastructure, tooling, and underground ecosystems.

By pivoting from the initial intrusion to an exposed attacker-controlled server, we observed the malware’s build pipeline, analyzed its internal logic, and connected the activity to wider underground communities, including Iranian- and Chinese-speaking ecosystems. This blog walks through the attack end-to-end, from initial access to attribution signals, and illustrates how modern threat actors operationalize open-source tooling at scale.

Key Takeaways

- Additional intelligence revealed threat actors’ identities as developers on GitHub, and “Offensive Security Tools” (OSTs) that can double as threat infrastructure

- Following this real-world attack chain highlights the importance of threat intelligence to provide a wide and complete picture on attacks

- Comprehensive threat intelligence requires visibility across diverse channels, including coding platforms, open-source ecosystems, and the deep and dark web channels

Attack Overview: From Compromised Server to Go Malware Attack Server

Initial Access and Main Payload

We deployed a high-interaction honeypot with a weak SSH password. A threat actor initiated a brute force attack against our misconfigured server and gained access with admin privileges.

Once authentication succeeds, an automated script behavior immediately pivots into environment profiling. It executed a standard battery of Linux commands, including:

- System identity: hostname, uname -a, uptime

- Process and service visibility: ps aux, netstat -tulpn

- Environment context: env, mount

- Connectivity checks: ping

The goal wasn’t gaining persistence at this stage, but a classification of the server. The threat actor wanted to quickly determine whether the compromised host is:

- Real and valuable

- Externally reachable

- Running services worth further exploitation

This “fast recon” pattern is extremely common in modern intrusion campaigns.

Pivoting from Our Honeypot to the Attacker’s Server

We traced the intrusion attempt against our honeypot to a server controlled by the attacker. That server was misconfigured: an internet-exposed Jupyter Notebook instance was openly accessible, allowing anyone to observe the attacker’s environment. This raised an immediate question – had the threat actor simply become reckless, or were they operating from a previously compromised victim server repurposed to launch attacks?

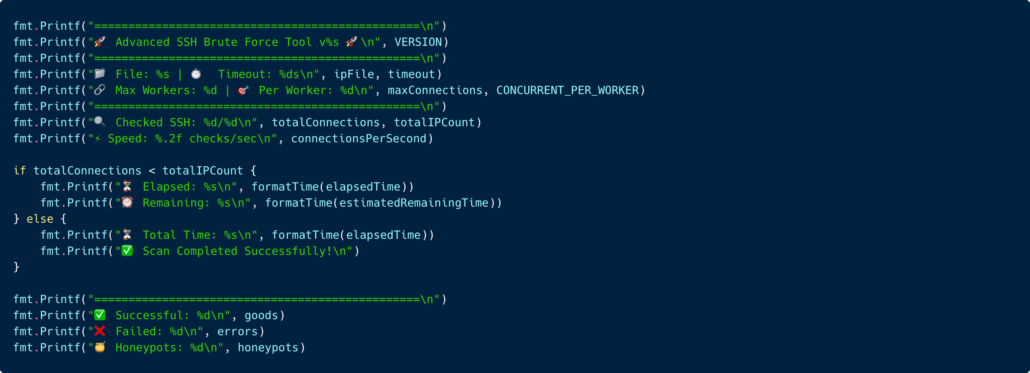

The exposed Jupyter Notebook provided rare visibility into the attacker’s workflow. It revealed that the threat actor was compiling a Go-based package and actively launching SSH brute-force attacks against our server and others. Among the artifacts on the system was a file named ssh.go, containing the following command:

The build command of the Golang SSH brute force malware

In the snippet above, you can observe how the attacker is installing golang and zmap (ZMap is a high-speed, stateless internet IPv4 scanner), building the SSH.go file, increasing the number of processes and file descriptors and running zmap on exposed servers with port 22 and running the SSH brute force tool with the results and a user password list.

SSH.go High-Level Overview

At its core, this tool is an SSH credential abuse and post-authentication reconnaissance framework written in Go. It is designed to:

- Attempt SSH authentication at scale using supplied credential lists

- Maximize throughput using aggressive concurrency

- Perform automated reconnaissance immediately after successful login

- Filter out deceptive environments using basic honeypot heuristics

- Log and categorize successful access for later exploitation

Unlike simplistic scripts, this malware shows operational intent; it is built to be reused, tuned, and integrated into broader attack workflows.

Input-Driven Attack Model

Rather than scanning the internet itself, the tool relies on external intelligence:

- A file containing IP:port targets

- A username list

- A password list

These inputs are combined into a credential matrix (username:password pairs), which are then tested across all supplied SSH endpoints.

This separation of scanning from exploitation is a common attacker design choice—it allows reuse of the tool across different campaigns without modifying code.

High-Concurrency SSH Login Attempts

The malware uses Go’s golang.org/x/crypto/ssh package to perform authentication attempts. Several notable traits stand out:

- Host key verification is explicitly disabled, allowing connections to any SSH server without trust validation.

- A worker pool design enables hundreds to thousands of concurrent login attempts, depending on configuration.

Timeouts are configurable, enabling tuning for slow or unstable networks.

From a defender’s perspective, this explains why brute-force traffic often appears as short-lived, high-volume bursts rather than sustained linear attempts.

Post-Authentication Reconnaissance

This part matches what we’ve seen on our honeypot.

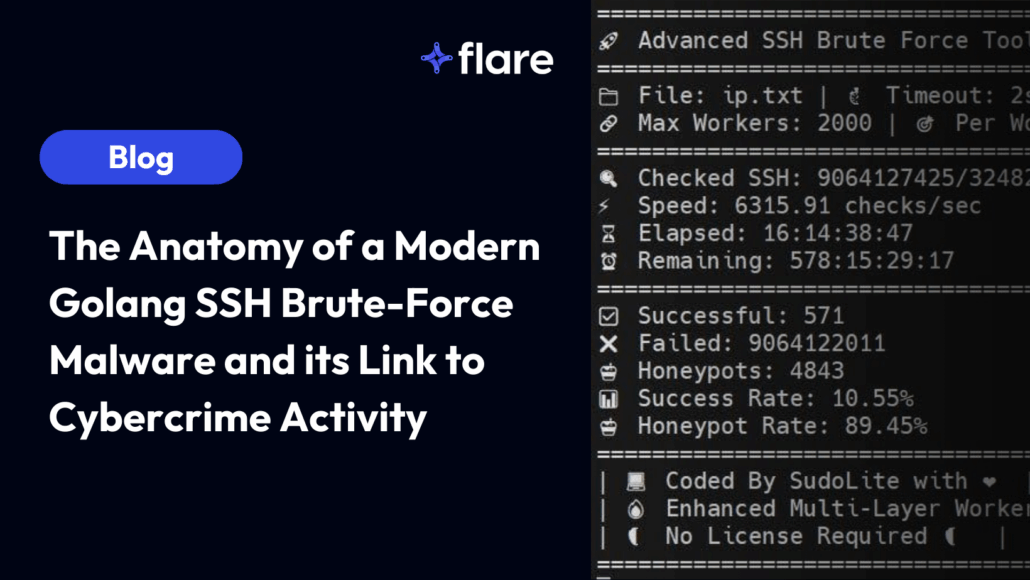

A code snippet from the ssh.go file illustrating what the malware print to screen

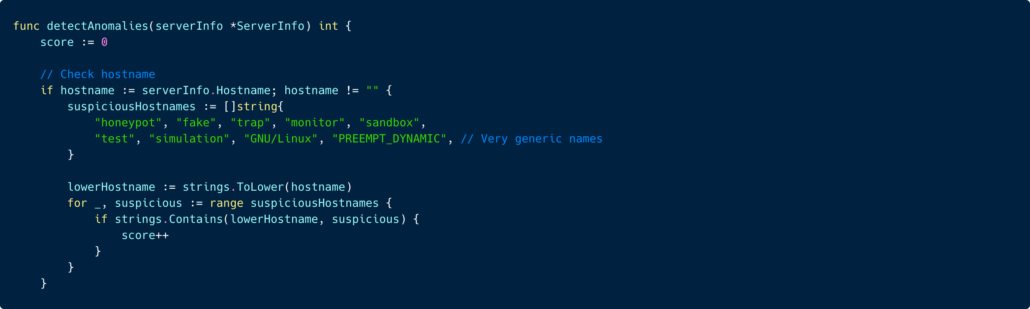

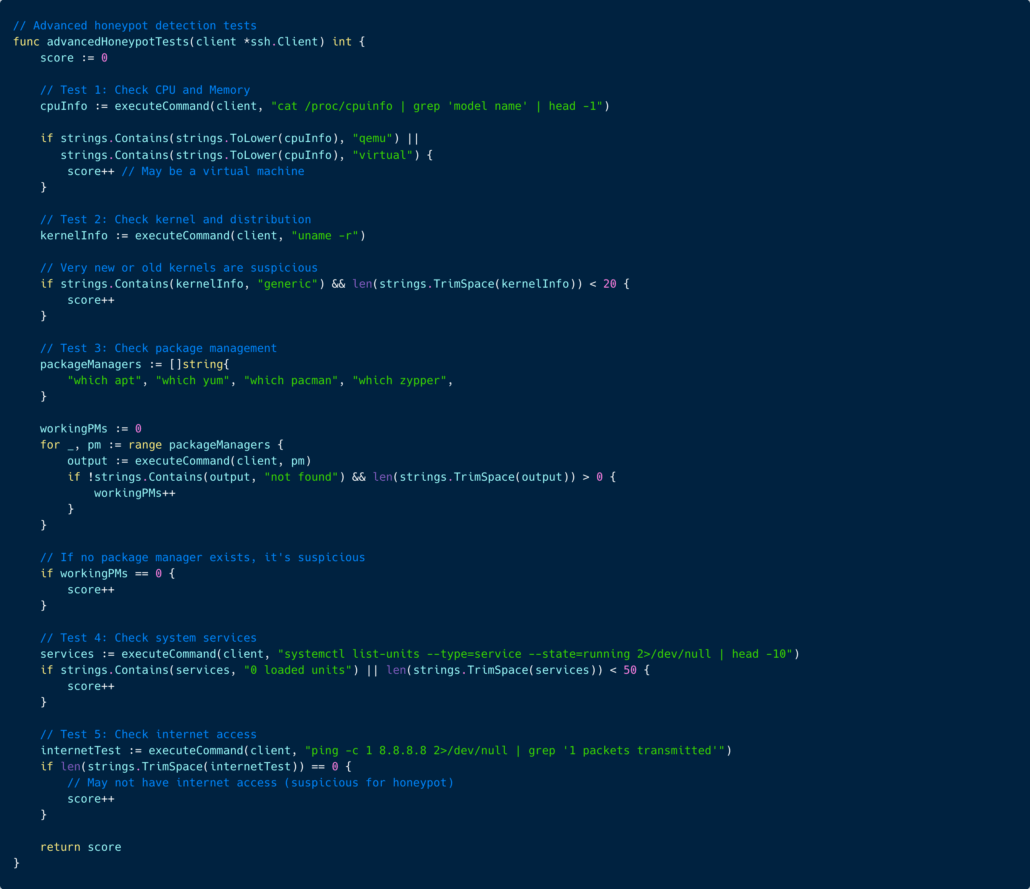

Honeypot Awareness (and its Limits)

Interestingly, the malware attempts to avoid wasting effort on deception environments.

It assigns a “honeypot score” based on signals such as:

- Known honeypot process names

- Suspicious filesystem behavior

- Unnaturally fast command responses

- Failed attempts to write temporary files

- Network behavior inconsistencies

Some of the honeypot detection logic the malware is using

If the score crosses a defined threshold, the target is flagged and excluded from the “good” results.

This is not advanced evasion – but it is good enough to eliminate many low-interaction honeypots, which explains why attackers increasingly bypass basic traps while still falling into more realistic ones.

Honeypot detection rules based on the system information and running processes

Artifacts and Logging

The tool is designed for operator usability, not just raw exploitation. It produces multiple local output files:

- Successful credentials

- Detailed host recon results

- Honeypot classifications

- Credential combinations

This reinforces an important point: many attackers think like system operators. They build tooling that supports triage, reuse, and downstream automation.

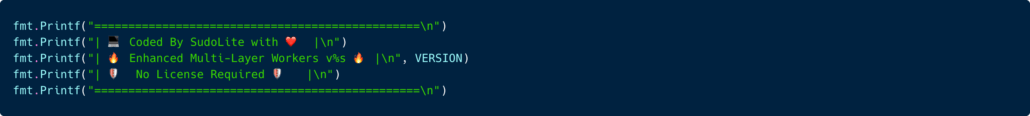

The malware’s output

Pivoting to Find the Developer

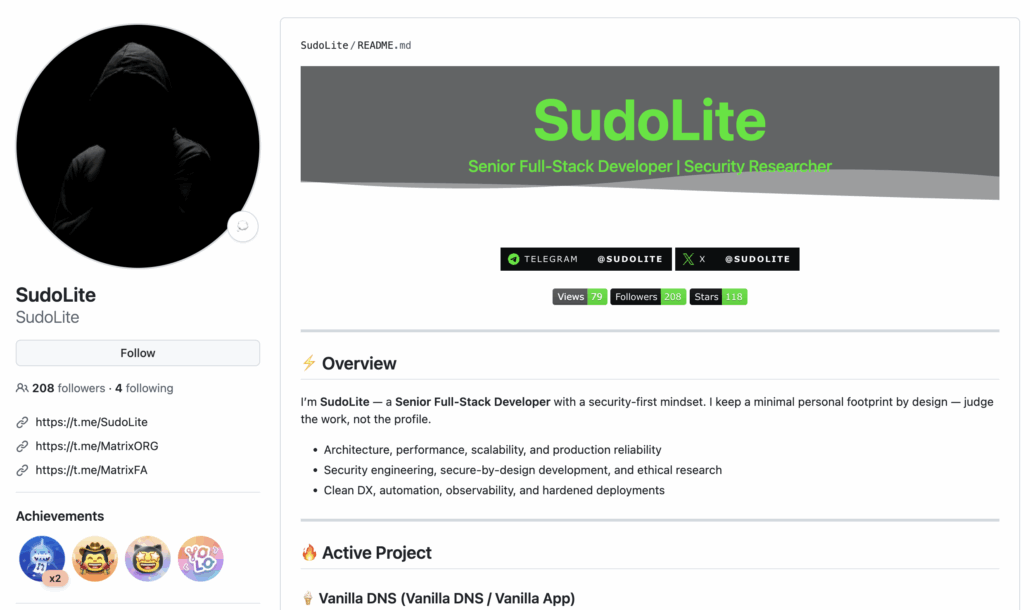

The signature of the coder of the malware is in this code, as illustrated before this tool was coded by SudoLite.

A “note” we found inside the malware declaring SudoLite as the author

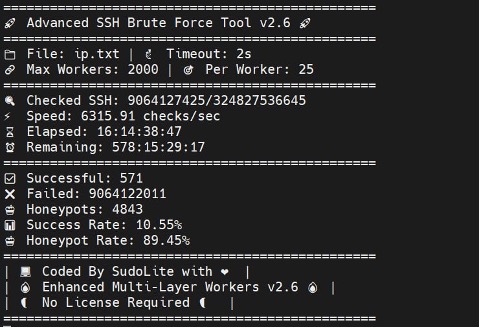

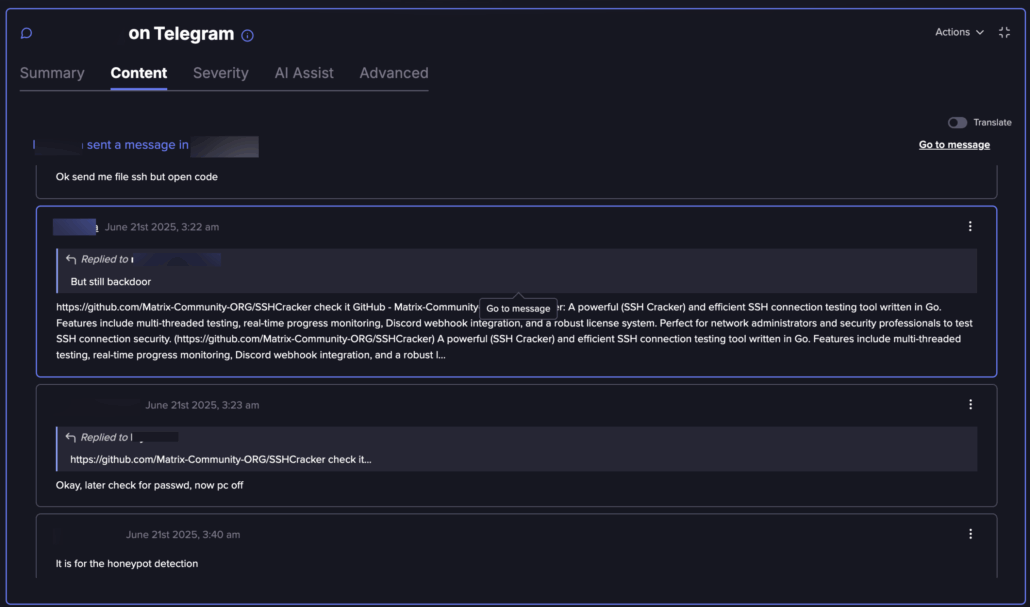

We utilized Flare to gather further intelligence on this threat actor. On Telegram, we observed several indications that this tool is actively used in the wild.

In the screenshot below, for instance, you can see an indication that this tool attempted brute force on an imaginary number of over 300 billion servers and gained successful SSH access to 5,414 of them, while marking 4,843 as honeypots.

These too-good-to-be-true figures put in question the authenticity of this underground post. This might be an exaggerated advertisement of the tool’s capabilities.

A screenshot collected by Flare indicating that this malware is active in the wild (Flare link to post, sign up for the free trial to access if you aren’t already a customer)

Further search led us to an Offensive Security Tool (OST) called “SSH Cracker,” published as open-source. In many references, it is published as a free OST for security purposes, but there is some criticism in the groups themselves pointing out it can serve as a backdoor and has weird features like honeypot detection, which is a very odd feature for security purposes.

Telegram discussion about the SSHCracker malware (Flare link to post, sign up for the free trial to access if you aren’t already a customer)

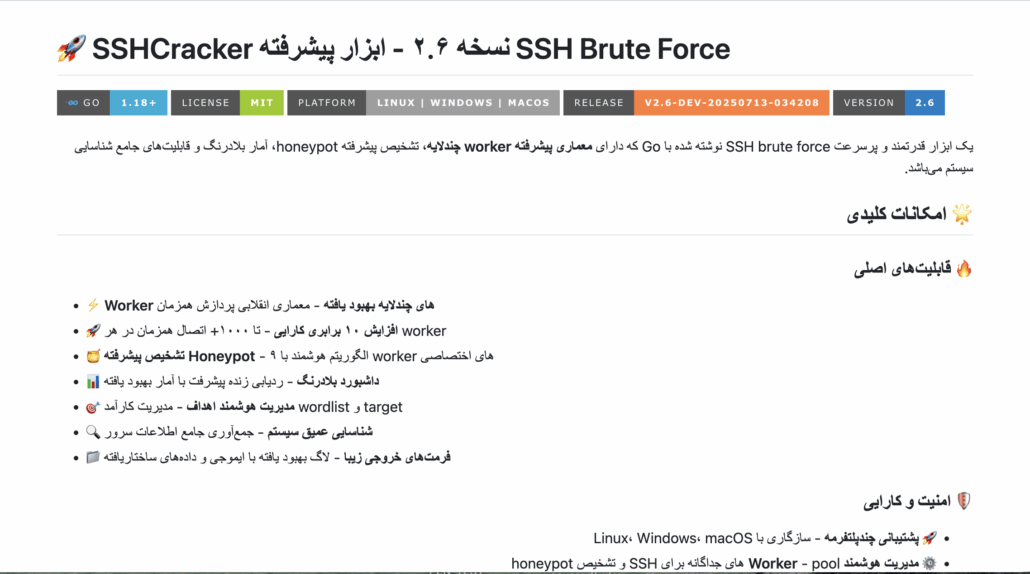

A screenshot from GitHub (Farsi) of the SSHCracker repository

A further analysis of the GitHub groups shows that there is a GitHub user by the name SudoLite who published this tool as an open-source under this GitHub organization “Matrix-Community-ORG.”

A screenshot from the GitHub account of SudoLite

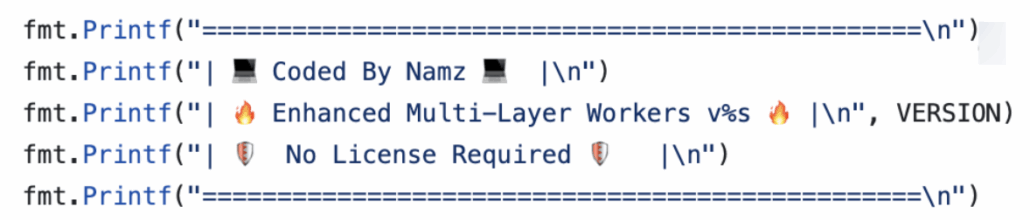

The tool itself was published as open-source around May 2025 and under the organization Matrix-Community-ORG and there’s constant revision and maintenance. Since then there’s been one fork by a user called “SATANFATHER.” In October 22, 2025, a user called “Namz,” uploaded a strikingly similar tool with minor modifications and wrote himself as the coder.

The modified version of SSHCracker by Namz

The key difference between the two versions is operational maturity: one allows reuse of an existing credential combo file and safely handles IP lists with or without explicit ports, while the other always regenerates credentials and assumes a rigid input format. In practice, this means the “Namz” version is more resilient, flexible, and better suited for repeated large-scale brute force runs, whereas the second is simpler but more fragile and prone to input-related failures.

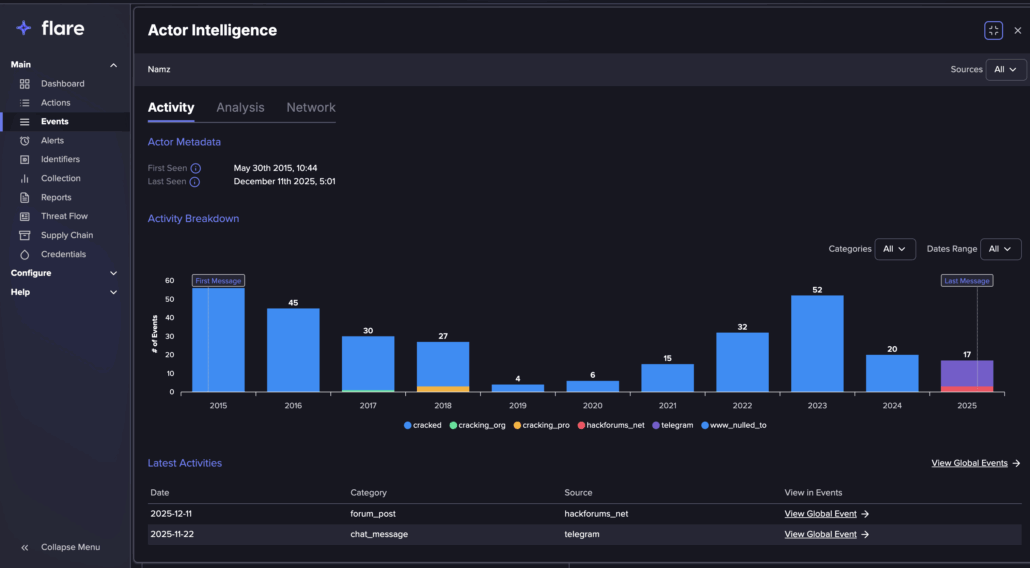

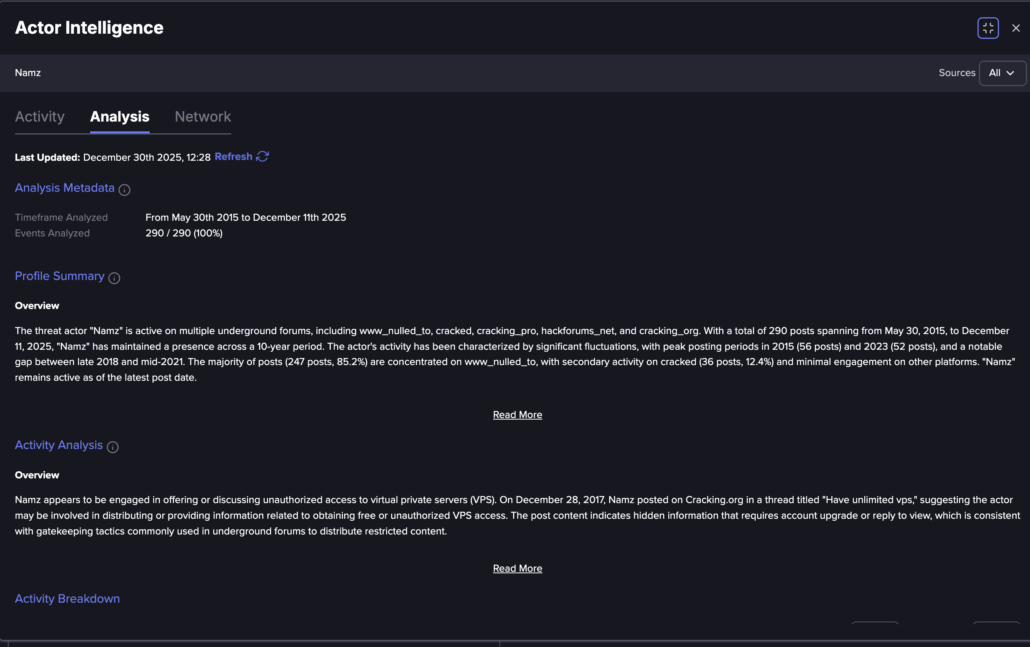

When searching for the activity of a threat actor named “Namz” on Flare there are many results, from various hacking tools related rooms in hacker forums to Telegram chat groups. There’s a strong link to Chinese speaking underground groups revolving around hacking activity.

Additional Threat Intelligence

In this blog, we found two links to supposedly underground activity, one by Farsi (Iran) speaking individuals and the other by a Chinese speaking threat actor. It genuinely looks like the Matrix-Community-ORG GitHub organization is linked to Farsi speaking developers who see themselves as security researchers. The GitHub page is linked to three Telegram groups.

Matrix Community Telegram group in Farsi

While the Matrix Community in English and Farsi genuinely look benign, the DDoS chat room looks awfully suspicious (to say the least):

- There are over 1,400 members in this group

- There is a lot of activity around hacking and DDoS attacks

- Members are seeking to hire other threat actors who are willing to attack for cryptocurrency payment

- There are threat actors who look for malicious tools

The threat actor Namz seems to have a long history of activity, at least since 2015. While we couldn’t find any indication the threat actor is linked to specific SSH brute force activity, there are many indications to high technological capabilities, including RDP brute force operation.

Namz activity breakdown on Flare (Sign up for the free trial to access if you aren’t already a customer)

Namz activity analysis (based on AI) (Flare link to post, sign up for the free trial to access if you aren’t already a customer)

MITRE ATT&CK Techniques Observed

The observed activity spans multiple stages of the MITRE ATT&CK framework, reflecting an intrusion workflow rather than an isolated brute-force event.

Initial access was achieved primarily through Valid Accounts (T1078), leveraging weak or default SSH credentials on exposed services. In parallel, misconfigured public-facing services such as internet-exposed Jupyter Notebook instances align with Exploit Public-Facing Application (T1190), enabling attackers to execute commands without authentication.

For Execution, the attacker relied heavily on Command and Scripting Interpreter: Unix Shell (T1059.004) to install packages, build tooling, and launch attacks. A notable technique was Compile After Delivery (T1027.004), where Golang source code was dropped onto compromised hosts and compiled locally, producing unique binaries per victim and evading static signature-based detection.

During Discovery, the malware performed rapid host profiling using System Information Discovery (T1082), Process Discovery (T1057), File and Directory Discovery (T1083), and Network Service Discovery (T1046). This “fast recon” phase was used to classify hosts, identify valuable targets, and avoid low-interaction honeypots.

Lateral Movement and Propagation occurred through continued SSH credential abuse, consistent with Exploitation of Remote Services (T1210) and Use of Alternate Authentication Material (T1550), as compromised systems were reused as pivot points to attack additional hosts.

Beyond compile-after-delivery, the Defense Evasion techniques include rudimentary honeypot detection heuristics (filesystem checks, timing analysis, and process inspection) falling under Obfuscated Files or Information (T1027) and low-effort evasion tactics aimed at bypassing basic deception environments.

Finally, the campaign aligns with Impact techniques such as Resource Hijacking (T1496) and Network Denial of Service (T1498), given the malware’s role in building scalable SSH access and its connection to underground communities advertising DDoS and botnet capabilities.

This mapping highlights how modern brute-force tooling blends credential abuse, automation, and evasion into a repeatable, operator-driven attack chain rather than a single-point exploit.

How Security Teams Can Shift their Defenses

Our investigation reveals how a seemingly routine SSH brute-force attack that is investigated on a daily basis in literally every SOC around the world, exposed a mature Golang-based malware ecosystem designed for large-scale credential abuse, post-authentication reconnaissance, and basic honeypot avoidance.

By analyzing attacker behavior on our honeypot and pivoting to a misconfigured attack server, we uncovered how the malware was compiled and executed in real time, how targets were triaged for value, and how results were logged for reuse in downstream campaigns. Further intelligence gathering linked the tool to dark web forums, Telegram groups, and overlapping developer identities, illustrating how open-source “security tools” can rapidly transition into active threat infrastructure.

Ultimately, this research underscores a critical defensive lesson: attackers now think like operators, and defenders must detect not just malware binaries, but also the behaviors, workflows, and infrastructure that enable these campaigns to scale.

Monitor for External Threats with Flare

The Flare Threat Exposure Management solution empowers organizations to proactively detect, prioritize, and mitigate the types of exposures commonly exploited by threat actors. Our platform automatically scans the clear & dark web and prominent threat actor communities 24/7 to discover unknown events, prioritize risks, and deliver actionable intelligence you can use instantly to improve security.

Flare integrates into your security program in 30 minutes and often replaces several SaaS and open source tools. See what external threats are exposed for your organization by signing up for our free trial.