“A thief may sleep full-fed with stolen bread, But flames will one day burn his bed.”

— Saadi Shirazi, The Rose Garden (Gulistan), 1258

According to TRM Labs’ 2025 Crypto Crime Report, illicit cryptocurrency transaction volumes reached at least $45 billion in 2024. Although that staggering sum covers every corner of the digital underground, including darknet retail, sanctions evasion, and outright cyber extortion, cybercrime remains one of its most powerful engines. Within that slice, Chainalysis estimates that ransomware operators alone extorted about $813 million from victims in 2024, a 35% decrease from the record setting $1.25 billion collected in 2023. For the first time since 2022, ransomware revenues declined, a shift that likely reflects the growing effectiveness of law enforcement operations that disrupted several major Russian-speaking groups such as LockBit.

Although ransomware earnings have fallen, the mystique surrounding Russian speaking cybercriminals and ransomware as a service outfits remains stronger than ever. These actors continue to command global attention not only because of their technical sophistication but also because of a persistent and often sensationalized media narrative that portrays them as omnipresent and unstoppable.

Beyond ransomware, Russian-speaking threat actors still profit from a wide spectrum of criminal enterprises. They broker initial access to compromised networks, operate bulletproof hosting services, develop and distribute infostealers such as Lumma and RedLine, resell stolen credentials on underground markets like Russian Market, run large scale cryptocurrency investment scams, and facilitate online drug trafficking. Each of these ventures generates substantial illicit income that must ultimately be laundered before it can be spent without legal or financial risk.

This image of the lavish, untouchable “Russian hacker” has been largely shaped by wanted posters, law enforcement statements, leaked chats, and sensationalist reporting. A notable example is Maksim Yakubets, alleged leader of Evil Corp, who became emblematic of this narrative after flaunting his wealth, most famously by driving a customized Lamborghini with a license plate that read THIEF in Russian.

Figure 1. Maksim Yakubets speaks to a policeman in front of his personalized Lamborghini.

While M. Yakubets embodied the stereotype through ostentatious display, more recent actors have reinforced it through scale and structure rather than spectacle. Figures such as Vitaly Kovalev, identified by German authorities as Stern, played a central role in the Trickbot and Conti ransomware operations, which reportedly extorted hundreds of millions of dollars from global victims. Likewise, Dmitry Khoroshev (aka LockBitSupp) and Oleg Nefedov (aka Tramp), the suspected minds behind LockBit and Black Basta respectively, have emerged as central architects of the RaaS model, coordinating industrial scale operations and setting up extensive laundering infrastructures that enabled them and their affiliates to convert illicit gains into real profit while avoiding direct exposure.

Yet despite the visibility and notoriety of these names, it is important to remember that they represent a narrow “elite” within a much broader ecosystem.

In reality, most actors in the Russian-speaking cybercriminal landscape operate at a much smaller scale. And even for the “successful” few, transforming cryptocurrency profits into clean, spendable money without attracting legal scrutiny or unwanted “protection” is often the most difficult and risky part of the entire operation. It requires not only patience and technical skill but also meticulous planning, front operations, and a working understanding of financial systems complex enough to frustrate even legitimate entrepreneurs.

This article explores the methods employed by Russian-speaking threat actors to launder their gains. Much like in Breaking Bad, the real challenge often begins after the money is made. Not with law enforcement kicking down the door, but with the slow, tedious realization that turning “dirty” cryptocurrencies into clean, usable income means engaging with the very systems cybercriminals sought to avoid. For many, this involves navigating obscure tax codes, registering front companies, and simulating legitimate business activity, often at the cost of paying significant taxes. In a world built on evasion and anonymity, having to play by the rules can feel like the most painful part of the operation.

Key Points and Observations on Russophone Threat Actors’ Money Laundering

- Most cybercriminals do not need full-scale laundering: The majority operate with modest profits that can be spent in cash or funneled through drops. Only a limited group of high-level actors such as ransomware operators, malware developers, and marketplace administrators generate enough income to require full laundering and legalization processes.

- Cryptocurrency cleaning does not equal income legalization: Obfuscating the origin of funds through mixers or swaps may hide traces on the blockchain, but it does not make the money legally usable. Legalization requires converting illicit proceeds into income that can be openly declared, invested, or spent without attracting scrutiny.

- Obfuscation and cashouts are widely accessible and structured: Mixers, anonymizing wallets, and no-KYC exchanges are easy to access. At least 44 services are active on top Russian-language forums, offering crypto swaps, mixing, and cash deliveries in the CIS, Europe, and the Middle East. Escrow deposits, typically around $100,000, are used to build customer trust, and many services operate under multiple brand identities controlled by the same groups.

- Legalization is the most difficult and sensitive phase: Turning illicit cryptocurrency into clean, usable income requires interaction with the financial system. While many threat actors discuss this stage on forums, detailed guidance is rare. Those who succeed tend to keep their methods secret due to the legal risks involved.

- Laundering strategies combine structured business setups and improvised schemes: The creation of businesses and the injection of illicit funds as apparent revenue is the most commonly discussed approach to income legalization. These operations are often supported by underground services offering forged documents and offshore company formation. Some actors also invest in real estate through informal deals, particularly in Middle Eastern countries with weak oversight. Others rely on improvised tactics such as NFT sales, staged casino winnings, or fabricated inheritance claims.

- Legalization is a potential vulnerability for sophisticated actors: Even technically skilled cybercriminals often misunderstand the intricacies of income legalization. Many underestimate the exposure risks linked to taxes, audits, and compliance. As LockBitSupp once noted, spending unlegalized money is what could attract law enforcement. The final step forces actors to engage with legal and bureaucratic systems they typically aim to avoid.

Cleaning and Cashing Out Cryptocurrency: The Easy Step

The “long awaited” moment has arrived. An unfortunate ransomware victim has paid the ransom to restore operations. A cryptocurrency wallet was emptied after being stolen by an infostealer from a naive user who installed an allegedly cracked video game. Banking credentials were harvested from an elderly person who mistook a phishing page for their bank’s website. In each case, a cybercriminal has successfully profited from malicious activity.

Outside of illicit trades like carding, most cybercriminal proceeds are typically converted into cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin, Monero, or others. But once that’s done, a key question arises: how can this cryptocurrency be safely turned into clean, usable currency?

The most common first step for financially motivated threat actors is to start by “cleaning” the cryptocurrencies by swapping them at an exchange or using a mixer (or tumbler), which is a service that obfuscates the origin of cryptocurrency by blending funds from multiple users, making it harder to trace the source and destination of the coins. Nevertheless, what seems logical for most cybercriminals is sometimes totally ignored by others, even the most technically advanced and successful.

For instance, in 2023, a LockBit affiliate named Ruslan Magomedovich Astamirov, was arrested in the USA because he received proceeds from ransoms directly on a wallet linked to his identity.

Figure 2. Simplified diagram of malicious revenue sources. Source: Cybercrime Diaries/Flare

Crypto Laundering for All: No Questions in the Russian-Speaking Underground

Less naive cybercriminals are using privacy focused wallets, exchanges, or mixers, that can be found on Tor network, on the clear web and on cybercriminal forums.

A famous example of such service was Tornado Cash mixer, which was widely used to launder stolen cryptocurrencies before being sanctioned by the U.S. Treasury in 2022. Presently on major Russian-language cybercrime forums, a substantial number of such services are advertised by threat actors specializing in cryptocurrency and cashouts.

As of May 2025, at least 44 exchanges offering cryptocurrency cleaning services, and in most cases cashout options as well, are actively promoted on top-tier forums such as Exploit, XSS, and the financial fraud focused DarkMoney. It must be noted that the majority of these services are also present on other important forums such as drugs related communities like RuTor, the fraud oriented Probiv, and general cybercriminal communities like LolzTeam and many others.

Figure 3. Exchanges, mixers and cash-out services accepting cryptocurrencies presently active on XSS, Exploit and DarkMoney. Source: Cybercrime Diaries/Flare

While a few services have operated for over a decade, new ones continue to emerge each year. Most disappear quickly, with only some successful and reputable managing to stay active beyond their first years. As in the BulletProof Hosting ecosystem, which we covered in a previous blog, Deciphering Black Basta’s Infrastructure from the Chat Leak, several exchange and mixer ‘brands’ that appear unrelated are in fact controlled by the same group of threat actors. This use of multiple brands is a deliberate commercial strategy to maximize visibility, attract different customer segments, and enhance overall profitability.

To operate on major Russian language cybercrime forums, exchange, mixers, and cashout services are required to deposit a significant amount of cryptocurrency or fiat into the forum’s escrow system. This serves as a guarantee of solvency in case of disputes with customers. Deposits range from $4,000 to as much as $300,000 on a single forum, with the average typically around $100,000 (approximately 1 BTC).

All of the studied services perfectly understand that the majority of their customers are cybercriminals wishing to clean cryptocurrencies obtained from illegal activities, often with high anti-money laundering (AML) scores. We have contacted several of them and pretended to be a potential customer that has received a substantial amount of Bitcoins from a ransomware ransom, this was not an issue for any of them.

Anonymized and translated excerpt from a discussion with an exchange operator:

Pentester:

Hi, I saw your profile on [a known Russian-language cybercrime forum]. I need advice and help with cashing out and laundering. I just received a payout from a “pentest” job (10 BTC), and I don’t know what’s the best way to convert it in Russia.

Popular Exchange/mixer/cashout service:

Hello.

Card transfers from 30,000 RUB: ~3.5% fee + 4% for “dirty” funds

- Courier delivery from 3 million RUB / $30,000: ~2.8% fee + 4% for “dirty”

- Tinkoff QR code from 400,000 RUB: ~8.5% fee + 4% for “dirty”

If the source has red tags (i.e., blacklisted), any tag = +10% fee. Same applies to yellow “High Risk Exchange” tags over 50%.

I can offer courier delivery.

You pay first. Once the funds are fully received, I place the order, and we arrange the location and time. Delivery usually takes 2–5 hours, but sometimes longer if couriers are overloaded. Pickup is secured by a token.

The token is a banknote of any currency and denomination showing the serial number and series. You send me a photo of the bill and bring it to the meeting to prove you’re the recipient.

While illicit mixers and exchanges may provide a sense of anonymity and security, a single infection with infostealer malware can compromise an entire obfuscation and laundering operation. Even if the infected system contains no sensitive personal data from the threat actor, such as when using a virtual machine hosted on a no-KYC hosting service, the presence of credentials for an illicit exchange in the logs can reveal which services were used and by whom.

Some of these illicit exchanges have created their own websites to help users carry out transactions. As with any online service, an infostealer infection can result in the theft of login credentials, session cookies, and browsing history, all of which may later appear on specialized Telegram channels and underground marketplaces.

In fact, while analyzing Flare’s database, we identified a substantial number of users who were infected by infostealers and whose stealer logs included access credentials for these illicit exchanges and mixing services. This offers valuable insight into which specific crypto obfuscation, cleaning, and cashout services are used by various users or entities. It also creates a unique opportunity to map relationships between these services and the individuals relying on them, despite the systems being designed to remain hidden.

Figure 4. Example of logs of users of illicit exchanges infected by an infostealer. Source: Flare

Breaking the Trail: From Cryptocurrencies Cleaning to Cashout

Upon receiving cryptocurrencies with questionable origins, such services often employ different methods like CoinJoin to obfuscate the transaction trail, aiming to disrupt the direct linkage between illicit funds and their source. CoinJoin, utilized by wallets such as Wasabi, combines multiple users’ UTXOs into a single transaction, making it challenging to trace specific inputs to outputs. However, this method doesn’t guarantee complete anonymity. Research indicates that with sophisticated analysis, it’s possible to identify patterns and potentially trace outputs back to their origins.

Figure 5. A cryptocurrency exchange and mixing service advertised on the XSS forum. The service claims that it can send money directly on bank accounts or deliver it in cash.

More advanced illicit services often utilize cross-chain swaps, such as converting Bitcoin (BTC) to Monero (XMR) and then to Ethereum (ETH), to obscure the origin of funds and evade AML detection systems. According to the U.S. Department of the Treasury this technique, known as “chain hopping”, complicates the tracking of transactions across different blockchains. Others rely on over-the-counter (OTC) brokers or create their own alternative exchanges, to sell “dirty” coins to unsuspecting buyers or accomplices in exchange for “clean” funds, often in regions with weak or no KYC enforcement.

Figure 6. An example of an exchange service that claimed on the XSS forum that it was able to provide clean cryptocurrencies to its customers by selling off the dirty ones to unsuspecting buyers on legitimate platforms such as Binance/Kraken/KuCoin.

In some obfuscation setups, cybercriminals receive “clean” crypto from a pre-filled liquidity buffer while their “dirty” coins are slowly recycled via mixers, shell accounts, or sold in small amounts to reduce the AML risk score. These scores rely on heuristics such as proximity to illicit wallets, number of hops, and velocity of movement. To improve scores, actors deliberately add temporal dilution (letting coins “age” over months) and fragment transactions to make detection harder.

The final stage of the obfuscation process, and one that is the hardest to track for investigators, is called “cash out,” the conversion of cryptocurrency into banknotes or fiat currency deposited in a bank account. As demonstrated in our earlier discussion with one of the leading exchange services, organizing such an operation is relatively easy in the former USSR, and even in parts of Europe and other regions. A notable recent example of such a service in Europe is the case of Ekaterina Zhdanova, a Russian national who led the Smart Group, a crypto money-laundering network that facilitated the conversion of illicit funds for various criminal entities, including UK-based drug gangs.

Figure 7. Example of a cashout service advertised on DarkMoney forum claiming it can deliver banknotes in Russia, CIS or Europe. Machine translated from Russian.

Figure 8. Neo banks are particularly targeted with many threat actors selling accounts for these institutions. Machine translated from Russian. Source: DarkMoney forum.

However, once the cashout is complete, a more complex challenge arises: how to spend the money without attracting unwanted attention from authorities. Hiding the malicious origin of cryptocurrency is one thing; efficiently laundering criminal proceeds and legalizing revenues is another entirely. As LockBitSupp (aka Dmitry Khoroshev) once noted on XSS at the height of his activity: “The most important, long and nasty thing – legalization, for law enforcement agencies of any country all sources of your income must be clear and transparent, everyone must know where your money comes from and that it is legal, as soon as you start spending unlegalized money, you stick your ears out of the crowd, which means you can be put under surveillance”.

Figure 9. LockBitSupp explained in November 2022 on XSS forum how he managed to remain anonymous. His 6th point emphasized the importance of legalization of income. Machine translated from Russian.

Laundering at Scale: Where the Real Challenges Begin

The question of how to legalize income, or more directly, how to launder money, often appears on major Russian language cybercriminal forums. However, this concern really applies to only a small fraction of threat actors. Most simply do not earn enough for laundering to become a serious issue, or do not always understand that it’s important. In reality, money laundering is primarily a problem for the more “successful” cybercriminals, such as operators of illicit services like ransomware as a service, malware as a service, bulletproof hosting, underground exchanges, as well as owners of cybercriminal forums and illicit marketplaces. It also concerns top tier ransomware affiliates, top malware developers, and certain niche specialists. For the rest of the cybercriminal ecosystem, a few thousand dollars per month, or less, can be easily spent in cash or moved through bank accounts registered under fake identities or so-called “drops,” a term in Russian slang referring to individuals who lend or sell their identity for financial operations.

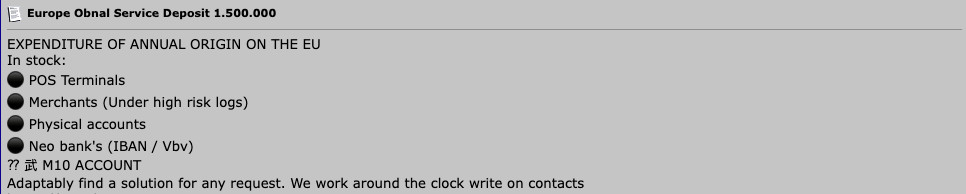

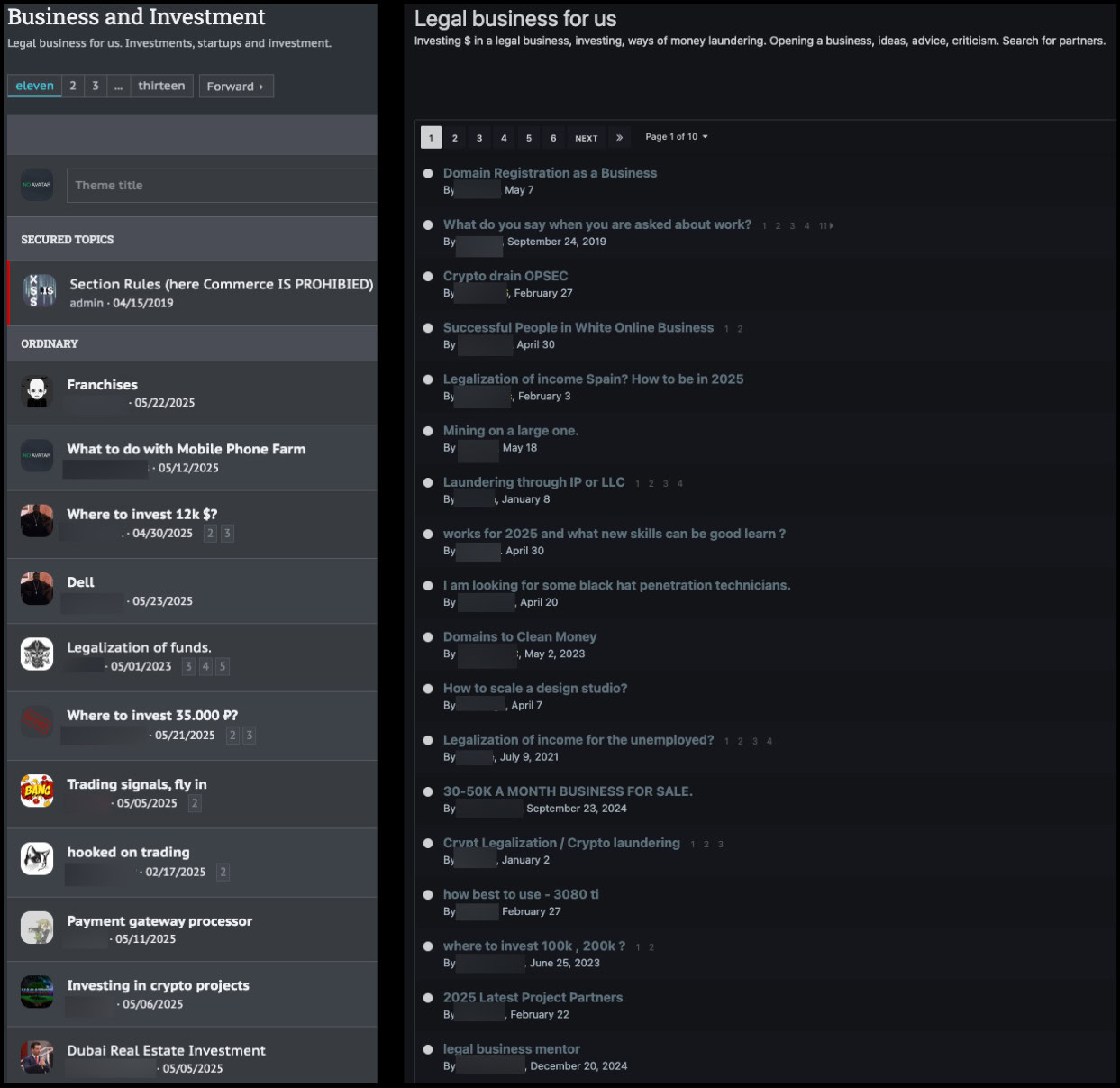

Figures 10 and 11. Examples of topics on XSS and Exploit about laundering and legal business investment.

Laundering Discussions on Russian-Language Cybercrime Forums: Hints Exist, Blueprints Don’t

Without delving into unnecessary details, let’s examine some of the most commonly discussed money laundering techniques on Russian-language forums such as XSS, Exploit and DarkMoney. While it is relatively easy to find services and information to assist with cryptocurrencies “cleaning” and cashout operations, no services openly advertise themselves as laundering solutions. It is very probable that cybercriminals who manage to conduct successful laundering operations keep their techniques to themselves and avoid giving specific details anywhere. As a result, many threat actors actively seek advice on how to proceed with legalizing their income, particularly in countries of the former USSR, but also in parts of Europe.

Several cases are genuinely amusing and revealing, exposing the widespread lack of financial and fiscal literacy among cybercriminals. For example, some are surprised to discover that a significant portion of their funds will be lost to taxes, service fees, or bribes during the laundering process. Others struggle to understand that spending large sums of illicit money without triggering attention from tax authorities or AML enforcement is far from straightforward. Many still fantasize about a silver bullet or a simple and risk-free way to legalize illicit gains, which, in reality, simply does not exist.

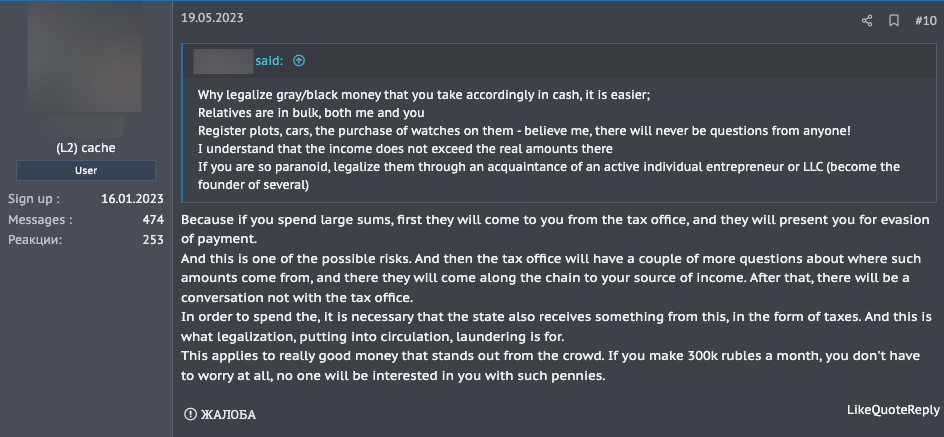

Figure 12. A threat actor explains on the XSS forum that it’s absolutely necessary to legalize an important amount of grey and black income to avoid scrutiny from law enforcement. Machine translated from Russian.

Figure 13. A threat actor gives hints about laundering techniques on the XSS forum. Machine translated from Russian.

Figure 14. A threat actor claims on XSS to have experience in laundering techniques but does not want to give specific details about his methods. Machine translated from Russian.

Top Methods for Money Laundering by Russophone Threat Actors

In a summary, the most frequently discussed ways of laundering money among Russophone threat actors can be described as follow:

- Creating and selling NFTs: In this case, a threat actor generates a digital “piece of art” and sells it for cryptocurrency through an anonymous wallet that they secretly control. While simple in appearance, this method carries significant risks, as tax authorities increasingly monitor NFT-related transactions. It cannot be repeated frequently or involve large sums without raising red flags.

- The death of a family member is also seen by some threat actors as a “good opportunity” to justify illicit funds: They do not hesitate to claim that they discovered large amounts of cash at the deceased’s residence in the inheritance documents.

- “Winning money” in an online casino: Here, the threat actor must collaborate with the casino operators, persuading them to participate in the laundering process in exchange for a fee. This approach is particularly risky, as it requires finding a willing casino and sharing sensitive personal or operational information with its administrators. (A similar case was shared by a threat actor who claimed to reside in a European country, where he allegedly managed to launder money through a real, physical casino. Other cybercriminals commenting on the story considered this method risky and viable only as a one-time solution. They noted that such casinos could easily attract regulatory scrutiny, potentially triggering fiscal audits of so-called “winners”.)

- A popular scheme, especially attractive a few years ago, involves purchasing real estate in a certain Middle Eastern country: According to testimonies from cybercriminals, it’s relatively easy to find developers there who accept cash or cryptocurrency and are willing to assist with paperwork and banking arrangements. After holding the property for a year, it can be sold, and the proceeds may be considered partially “clean” within that jurisdiction. However, justifying the origin of those funds in other countries remains problematic.

- Ultimately, the most popular but also the most complex legalization strategy mentioned by cybercriminals is the creation of a legitimate business.

- For lower-income threat actors, sole proprietorship in the field of dematerialized services is often considered the most suitable option, especially if the activity is unrelated to IT.

- For wealthier and more ambitious individuals or groups, establishing one or several businesses with real operations and falsified accounting is a widely discussed method. This approach is supported not only by claims from prominent threat actors on cybercrime forums, but also, as we will see, by real-world examples involving LockBitSupp and Tramp, the respective masterminds behind the RaaS groups LockBit and BlackBasta.

Figure 15. Main money laundering techniques discussed by Russian-speaking threat actors. Source: Cybercrime Diaries/Flare

Laundering Entrepreneurs: The Cases of LockBitSupp and Black Basta Administrators

Following the unmasking of the suspected administrators behind the LockBit and Black Basta ransomware operations, it became possible to uncover more details about them, especially since a great deal of information about entrepreneurs and business owners is publicly accessible in Russia. What emerges from the business activities of Dmitry Khoroshev (LockBitSupp – LockBit) and Oleg Nefedov (Tramp – Black Basta) is that their main strength both in their cybercriminal and business endeavors lies not in exceptional technical expertise, but in outstanding organizational capabilities.

The Black Basta leaks revealed that Oleg Nefedov was not only leading this cybercriminal organization but also operating several restaurant related businesses. He also appeared to be well connected with illicit cryptocurrency exchanges active in Moscow, which enabled him to efficiently organize the cashing out of large sums and subsequently launder the proceeds. Interestingly M. Nefedov’s wife is also very probably involved in this laundering operation as she also owns a restaurant business.

The involvement of family members in income legalization schemes is actually quite common and frequently discussed on cybercriminal forums. It is not unusual for cybercriminal’s relatives to suddenly develop a taste for entrepreneurship or to occupy high-paying executive positions in companies ultimately controlled by the threat actor.

Figure 16. Business activity of Oleg Nefedov (Tramp – BlackBasta) and his wife. Source: Cybercrime Diaries/Flare

The de-anonymization of Russian national Dmitry Khoroshev as LockBitSupp by law enforcement in 2024 also provided a small insight into the laundering operations of this multimillionaire. Although less information is available compared to other cases, it appears that M. Khoroshev has operated, and still is operating, as a sole proprietor in the online advertising sector. He also founded an e-commerce clothing store that was officially closed on September 30, 2022.

Notably, the following statement appears in the online registry entry for this company: “Information is unreliable. Results of a verification of the accuracy of the data contained in the EGRUL about the legal entity”. This suggests that Russian tax authorities identified some of the company’s registered details, such as its address, directors, or founders, as false or unverifiable. In other words, it may indicate that the company was recognized as a shell entity which highlights once again that illicit income legalization operations are not always simple.

Finally, it is likely that M. Khoroshev is using other, still undiscovered, channels to launder money, possibly through entities registered under fake names or those of relatives.

Figure 17. Business activity of Dmitry Khoroshev (LockBitSupp). Source: Cybercrime Diaries/Flare

Figure 18. Archived version of the e-commerce clothing store that belonged to M. Khoroshev.

Final Thoughts: The Cost of Clean Money

Laundering illicit cryptocurrency is not the glamorous final act of a cybercriminal’s heist; it is complex, costly, and risky. While technically perfectly possible, the process becomes significantly harder without trusted intermediaries, access to laundering networks, or the ability to simulate legitimate business activity without raising suspicion.

As this blog highlights, although initial obfuscation and cashout may be relatively easy to organize thanks to a thriving ecosystem of mixers, underground exchanges, and cashout services the real challenge begins when attempting to convert these funds into clean, usable income within the legal economy.

For the majority of actors in the Russophone cybercrime underground, this stage remains out of reach or irrelevant. But for the small minority who earn large sums, legalization becomes a necessity if they wish to fully use the proceeds of their criminal activity. Whether through shell companies, restaurants run by family members, or questionable e-commerce ventures, the transition from digital assets to legitimate revenue demands more than technical skill. It requires patience, bureaucracy management, and a deep understanding of how to operate within the same financial and regulatory systems these actors often exploit.

Ironically, the more successful the cybercriminal, the closer they must get to the world they once sought to evade. As LockBitSupp once wrote, the greatest exposure may not come from hacking into networks or collecting ransoms, but from spending unlegalized money. In the end, laundering dirty crypto is as much an organizational challenge as it is a high-stakes balancing act between discretion and greed.

Dig Further into Cybercrime with Flare Academy

Interested in following more cybercrime research? Check out Flare Academy’s training sessions, which are led by cybersecurity researchers. Check out the upcoming sessions here.

We also offer the Flare Academy Discord Community, where you can connect with peers and access training resources from the Flare Academy training.

Can’t wait to see you there!

Sources

[1] TRM, “2025 Crypto Crime Report,” 2025, https://www.trmlabs.com/resources/reports/2025-crypto-crime-report#:~:text=The%202025%20Crypto%20Crime%20Report,payments%20soared%20to%20record%20highs

[2] Chainalysis Team, “Crypto Ransomware 2025: 35.82% YoY Decrease in Ransomware Payments,” Chainalysis (blog), February 5, 2025, https://www.chainalysis.com/blog/crypto-crime-ransomware-victim-extortion-2025

[3] “Law Enforcement Disrupt World’s Biggest Ransomware Operation,” Europol, February 20, 2024, https://www.europol.europa.eu/media-press/newsroom/news/law-enforcement-disrupt-worlds-biggest-ransomware-operation

[4] Flare, “Infostealer Malware: An Introduction,” Flare | Cyber Threat Intel | Digital Risk Protection (blog), November 13, 2024, https://flare.io/learn/resources/blog/infostealer-malware

[5] “Treasury Sanctions Evil Corp, the Russia-Based Cybercriminal Group Behind Dridex Malware,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, December 5, 2019, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm845

[6] WIRED, “Cops in Germany Claim They’ve ID’d the Mysterious Trickbot Ransomware Kingpin,” May 30, 2025, https://www.wired.com/story/stern-trickbot-identified-germany-bka

[7] “Lockbit Ransomware Administrator Dmitry Yuryevich Khoroshev,” United States Department of State (blog), May 7, 2024, https://www.state.gov/transnational-organized-crime-rewards-program-2/lockbit-ransomware-administrator-dmitry-yuryevich-khoroshev

[8] “Ransomware : de REvil à Black Basta, que sait-on de Tramp ?,” LeMagIT, March 1, 2025, https://www.lemagit.fr/actualites/366619807/Ransomware-de-REvil-a-Black-Basta-que-sait-on-de-Tramp

[9] “Office of Public Affairs | Russian National Arrested and Charged with Conspiring to Commit LockBit Ransomware Attacks Against U.S. and Foreign Businesses | United States Department of Justice,” June 15, 2023, https://www.justice.gov/archives/opa/pr/russian-national-arrested-and-charged-conspiring-commit-lockbit-ransomware-attacks-against-us

[10] “U.S. Treasury Sanctions Notorious Virtual Currency Mixer Tornado Cash,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, August 8, 2022, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0916

[11] Oleg O, “50 Shades of Bulletproof Hosting – BPH Landscape on Russian Language Cybercrime Forums.,” Cybercrime Diaries, July 8, 2024, https://www.cybercrimediaries.com/post/50-shades-of-bulletproof-hosting-bph-landscape-on-russian-language-cybercrime-forums

[12] Protos, “US Government Spooks Have Cracked ‘anonymous’ Bitcoin Wallet Wasabi,” Protos (blog), March 14, 2022, http://protos.com/bitcoin-mixing-coinjoin-wasabi-chainalysis-samourai-privacy-wallet

[13] U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY, “Illicit Finance Risk Assessment of Decentralized Finance,” April 2023, https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/DeFi-Risk-Full-Review.pdf

[14] Dilip Kumar Patairya, “Cointelegraph Bitcoin & Ethereum Blockchain News,” Cointelegraph, March 18, 2025, https://cointelegraph.com/explained/crypto-and-money-laundering-what-you-need-to-know

[15] Elliptic, “Typologies Report 2024,” 2024, https://www.elliptic.co/hubfs/Elliptic%20Typologies%20Report%202024.pdf

[16] BBC, “Russian Crypto Criminals Helped UK Drug Gangs Launder Lockdown Cash,” December 4, 2024, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c70ezyrep1go

[17] Oleg O, “Black Basta Chat Leak – Organization and Infrastructures,” Cybercrime Diaries, March 5, 2025, https://www.cybercrimediaries.com/post/black-basta-chat-leak-organization-and-infrastructures