The SolarWinds incident has received extensive coverage over the past few months. For those that have missed the thousands of news stories published on this incident, it was best summarized by Business Insider as below:

“In early 2020, hackers secretly broke into Texas-based SolarWinds’ systems and added malicious code into the company’s software system. Solarwinds has 33,000 customers […]. Beginning as early as March of last year, SolarWinds unwittingly sent out software updates to its customers that included the hacked code. The code created a backdoor to customer’s information technology systems, which hackers then used to install even more malware.”

The SolarWinds incident was back in the news again this week because of the CEO’s testimony in front of Congress. During the testimony, he claimed the hack was caused by an intern who had posted a password to a file server on their own personal GitHub left open on the internet. Malicious actors allegedly found the password, used it to infect SolarWinds’ software in a supply-chain attack, and then took over multiple large organizations and institutions worldwide.

Moving beyond the ethics of pointing the finger at a single employee – or intern, this story exposes many of the challenges most organizations face, and serve as a reminder of the agility and speed of malicious actors.

Finding A Needle (Password) in A Haystack (Code Repository)

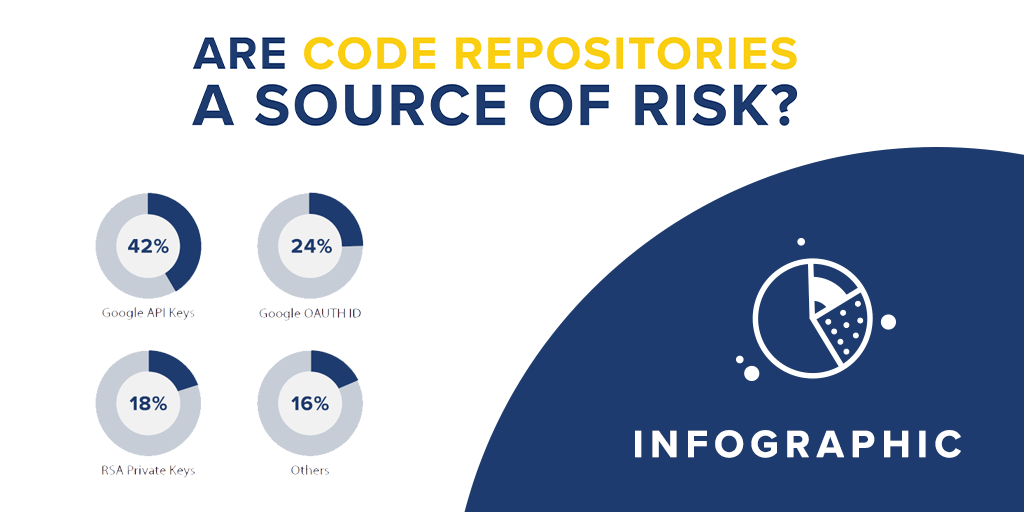

At first, it may look nearly impossible for malicious actors to go through an entire code repository to identify leaked technical secrets, such as passwords and API keys. It would seem even more impossible for malicious actors to do so in a matter of minutes, or hours. There is however much evidence that this is happening on a daily basis, and that code repositories represent a significant risk for organizations.

Last November, we reported on the story of a programmer who mistakenly published his AWS private access keys. Within hours, malicious actors had spun up virtual machines, and were charging his credit card to purchase computing power to mine cryptocurrencies.

This story is telling, as the malicious actors sprung into action within hours of the leaked technical secret being published. This suggests that malicious actors have developed tools to monitor code repositories, and that their combined efforts mean that at least one of them is likely to find a technical secret, hours after it is published. While hundreds or thousands of malicious actors may be doing some monitoring, only one of them needs to succeed to lead to the victimization of a company.

We are as humans very bad at estimating risks. Some risks that are extremely low – like dying in an airplane accident – create much stress in people, while risks that are much higher – being involved in a car accident – are not even on the radar of most. Not training employees, interns and partners about the risks of code repositories is akin to car accidents. It is of much higher risk, but too often not prioritized among the thousands of tasks of cybersecurity teams.

Enforcing Policies Is Mandatory, Not Optional

The SolarWinds incident was also a good example of the need to enforce policies. The password that was at the root of the file server exploitation was in all lowercase characters, with numbers at the end. More concerning, it would have been trivial to guess as it contained the name of the company.

The password apparently did not meet the company’s policy for strong password and was published online again against company policy. There are no mentions in the news of a policy to use multiple factor authentication for sensitive resources, but it would be expected for any large organization to have such a policy.

SolarWinds’ CEO publicly complained that the policies regarding identity management, and passwords, were unfortunately not followed. This showcases how security is not a goal, but a process. Security needs to be lived every day of every year. Developing security policies is a good start, but there needs to be accountability for who is in charge of implementing the policies, and enforcing them.

This stresses the need for organizations to trust their employees, interns and partners, but also to verify, as one famous president once said. This translates to organizations monitoring their digital footprint to identify how policies are implemented in practice, and detect any unwilling leak of technical secrets.

In an infographic, we presented past research on the time needed to detect, and take down leaked technical secrets. What is striking here is that 6% of leaked secrets are removed within an hour of disclosure, and 12% within a day. There definitely seems to be two classes of organizations in the world, with a minority actively monitoring their digital footprint. These organizations are less likely to end up victims of supply-chain attacks, and provide us with a clear path to follow to keep our employees, customers and partners secure.